There is no better birthday gift I could have given myself than two hours of 20th-century American orchestral music. Lucky for me, the Boston Symphony Orchestra offered just that this weekend, featuring three pieces by American composers - Three Places in New England by Ives, Three Illusions for Orchestra by the venerable Elliot Carter, and Gershwin’s Piano Concerto in F - and one by an émigré, Time Cycle for Soprano and Orchestra by Lukas Foss.

There is no better birthday gift I could have given myself than two hours of 20th-century American orchestral music. Lucky for me, the Boston Symphony Orchestra offered just that this weekend, featuring three pieces by American composers - Three Places in New England by Ives, Three Illusions for Orchestra by the venerable Elliot Carter, and Gershwin’s Piano Concerto in F - and one by an émigré, Time Cycle for Soprano and Orchestra by Lukas Foss.The concert was anchored by the Ives and Carter triptychs, which is fitting, as Ives encouraged the teen-aged Carter to pursue music. By all accounts, Ives was a ball-buster, and a man who could get things done. (Oh, to be able to write with that level of courage!) Three Places in New England, the opener for this performance, is a glorious, dignified representation of the visionary quality of Ives’s work. Far ahead of the avant-garde that attempted to forge a “new” kind of music in the middle part of the century (Three Places was written between 1912 and 1917) the piece is built of a translucent texture that is stripped away like layers of onion skin to reveal a seemingly never-ending depth, but never gets convoluted.

T. J. Medrek, BSO embraces American masters (Boston Herald, October 7) Richard Dyer, BSO delights with American fare (Boston Globe, October 8) Anthony Tommasini, Levine and the Boston, Still Made for Each Other (New York Times, October 11) Alex Ross, Boston by a Mile (The Rest Is Noise, October 11) Anthony Tommasini, The Growing Impact of the Levine Era (New York Times, October 12) |

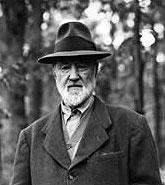

Elliot Carter, who is damn near 100 years old and still writing, supplied the first in a number of pieces the BSO commissioned for its 125th anniversary. Each of the 180-second Three Illusions for Orchestra (which opened the second half of the concert) are program pieces that display concise, idiomatic writing that are actually easily digestible at a first listening (for me at least – my fiancée, a DMA voice candidate at the New England Conservatory, shared the experience of most of the septuagenarians around us by describing the first movement thusly: “…ninety seconds of ambient noise, at which point, someone throws a bowling ball into the percussion closet…”). Carter’s piece, like the Ives, brought to the fore the strengths of the sections (most notably the strings) in conversation with each other, and the BSO rose gracefully to the demands of the clever orchestration.

Elliot Carter, who is damn near 100 years old and still writing, supplied the first in a number of pieces the BSO commissioned for its 125th anniversary. Each of the 180-second Three Illusions for Orchestra (which opened the second half of the concert) are program pieces that display concise, idiomatic writing that are actually easily digestible at a first listening (for me at least – my fiancée, a DMA voice candidate at the New England Conservatory, shared the experience of most of the septuagenarians around us by describing the first movement thusly: “…ninety seconds of ambient noise, at which point, someone throws a bowling ball into the percussion closet…”). Carter’s piece, like the Ives, brought to the fore the strengths of the sections (most notably the strings) in conversation with each other, and the BSO rose gracefully to the demands of the clever orchestration. The closing pieces of each half - the Foss and Gershwin, respectively – were a harder sell. Time Cycle for Soprano and Orchestra, by Lukas Foss (whose long history with the Boston Symphony was celebrated all over the program notes), was performed with stunning emotion by the generally stunning Dawn Upshaw. The piece, which really should have been scored for a chamber ensemble, consisted of four art songs written around texts (two English, two German – the composer’s native tongue) musing on perspectives of time. Upshaw breathed life into the texts with her own emotional pendulum that likewise left plenty of headroom. My fiancée explained to me some of the controversy surrounding Upshaw’s “emotional modification” as opposed to technically accepted practices of dealing with 20th-century works, but I felt as though Upshaw really dug into those texts that were otherwise mired in a thick mud of writing for an ensemble larger than the purpose of the piece. There were also moments of beautiful and romantic clarity, found especially in the smart orchestrations of the first two songs. Creatively doubling the voice with clarinet and harp, for instance, ingratiated the vocal line into the texture of the ensemble. Things sort of came crashing down in the third movement, however, when the language and the sentiment changed, and an Alban Berg-ish “I am, at heart, a miserable, introspective German, and don’t you forget it” attitude descended on the work – a downer from which things never recovered.

The closing pieces of each half - the Foss and Gershwin, respectively – were a harder sell. Time Cycle for Soprano and Orchestra, by Lukas Foss (whose long history with the Boston Symphony was celebrated all over the program notes), was performed with stunning emotion by the generally stunning Dawn Upshaw. The piece, which really should have been scored for a chamber ensemble, consisted of four art songs written around texts (two English, two German – the composer’s native tongue) musing on perspectives of time. Upshaw breathed life into the texts with her own emotional pendulum that likewise left plenty of headroom. My fiancée explained to me some of the controversy surrounding Upshaw’s “emotional modification” as opposed to technically accepted practices of dealing with 20th-century works, but I felt as though Upshaw really dug into those texts that were otherwise mired in a thick mud of writing for an ensemble larger than the purpose of the piece. There were also moments of beautiful and romantic clarity, found especially in the smart orchestrations of the first two songs. Creatively doubling the voice with clarinet and harp, for instance, ingratiated the vocal line into the texture of the ensemble. Things sort of came crashing down in the third movement, however, when the language and the sentiment changed, and an Alban Berg-ish “I am, at heart, a miserable, introspective German, and don’t you forget it” attitude descended on the work – a downer from which things never recovered.The second guest soloist for the program was pianist Jean-Yves Thibaudet, who took up the diva slack that Upshaw left backstage (his bio actually talked about who does his concert wardrobe). Thibaudet’s playing had no headroom – when he got louder, the fast notes became muddled, and he rushed badly. The sensitivity he displayed in the more tender moments of the piece, however, were very moving. At the first entrance of the piano – on that delicately static, syncopated melody – the whole room absolutely melted. More problems crept up on both sides of the stage when the “swing” sections came into play. Swing in orchestral settings sounds bad, unless it’s done correctly, and it never is. It’s like when white choirs try to sing Negro spirituals – something is horribly lost in the translation. Thibaudet’s idea of swing and Levine’s idea of swing were not the same.

The Boston Symphony is repeating this program on October 8 at 8 pm in Boston, and again on October 10 at 8pm in Carnegie Hall.

Alright, now that's a really good review! I love it when you guys write reviews that enable (?)(uh oh) me to feel as if I were there. I esp. liked the part about the concept of jazz headroom, who had it that night, who didn't, and who the real "diva" was.

ReplyDeleteAccurate, clever, angry and/or gushing, ionarts is the place on the web for non-stop vicarious classical music thrills. Art, too.

The same night, another work of Carter's - Spheres (I think) - saw its premiere in Chicago under Barenboim. 'Tis good to be 97 and kicking.

ReplyDeleteYou're thinking of Carter's "Soundings" written for Barenboim as both pianist and conductor. Notes to the work are at the Carnegie Hall website, as well as, no doubt, the Chicago web-site.

ReplyDeleteAs for other Chicago premieres of Mr Carter's works (from Carnegie Hall website):

"In Chicago, Carter has found one of his most important champions in Daniel Barenboim. They met for the first time when the composer went to that city in 1994 for the world premiere of Partita, which the Orchestra had commissioned. Since then Barenboim has led Chicago Symphony performances of Adagio Tenebroso and Allegro Scorrevole (which, along with Partita, form the triptych Symphonia), and he has conducted the world premieres of the Cello Concerto, with Yo-Yo Ma, in September 2001, and Of Rewaking, with Michele DeYoung, in May 2003."

BTW, Mr Carter is only a young 96 and ten-twelths...

Also BTW, the Boston Symphony's concert in Washington, next March 11, presented by WPAS, is even stronger, in my opinion, than the one Frank reviews:

ReplyDeleteR. Strauss: Till Eulenspiegel’s Merry Pranks

Peter Lieberson: Neruda Songs (with Mezzo-soprano Lorraine Hunt Lieberson)

Elliott Carter: Three Illusions for Orchestra

Beethoven: Symphony No. 7

What other orchestras in the world today come close to the strength of the BSO's programming and commitment to a living orchestral culture?

uh... you mean "what other AMERICAN orchestras" ?? And it is surely not the BSO that's to hail... it is Levine.

ReplyDeletejfl

I left it intentionally vague, now that some European [and Russian] orchestras are following most American orchestras down the path of the warhorse and fear of the [classical] new. What's your favorite non-American orchestra and conductor, Jens, and what is your favorite program(s) that this orchestra will be playing this season? (I hope the program will include at least one, if not two works by living composers.)

ReplyDeleteWith Maazel having left and Jansons at the helm of the Bavarian Radio SO... it is difficult to think of better. But I honestly don't know the scene well enough to pick any one... There are six good orchestras (soon only five) in Munich alone - SOMEONE's gotta be playing something interesting. And in Berlin they are crazy, half of the time, anyway - Rattle has flaws but he's a good programmer. Zinman in Zurich. Bertran de Billy wherever he is. Nagano with his band... Here's something from JUST UNTIL DECEMBER for the BRSO/BRPO: Dallapicola, Zeller, Hartmann, Schweinitz, Tippett, Webern, Berg, Bartok, Langaard, Hartmann, Killmayr, Etoevoes, Rihm - and admittedly, the program is still a lot more conservative than I would have thought.

ReplyDeleteCan you explain what you mean by this? I'm a big Upshaw fan, but I know she has her critics.

ReplyDeleteMy fiancée explained to me some of the controversy surrounding Upshaw’s “emotional modification” as opposed to technically accepted practices of dealing with 20th-century works