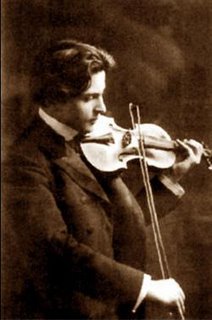

Remembering Enescu

Romanian composer George Enescu (1881–1955) -- or Georges Enesco, as he styled himself in France, his adopted home -- died 50 years ago. This weekend, the Barry S. Brook Center for Music Research and Documentation at CUNY and the Mannes College of Music are hosting a conference and series of performances in Enescu's honor. I was thrilled by Hilary Hahn's performance of this composer's third violin sonata when she played with Natalie Zhu at the Kennedy Center earlier this month. (Jens liked it, too.) That piece is on the festival's final concert, on December 4 at 8 pm, in Merkin Concert Hall. Violinist Sherban Lupu and pianist Ilinca Dumitrescu will also play several other Enescu pieces I would relish the chance to hear live, including the suite Impressions d’enfance (1940).

Romanian composer George Enescu (1881–1955) -- or Georges Enesco, as he styled himself in France, his adopted home -- died 50 years ago. This weekend, the Barry S. Brook Center for Music Research and Documentation at CUNY and the Mannes College of Music are hosting a conference and series of performances in Enescu's honor. I was thrilled by Hilary Hahn's performance of this composer's third violin sonata when she played with Natalie Zhu at the Kennedy Center earlier this month. (Jens liked it, too.) That piece is on the festival's final concert, on December 4 at 8 pm, in Merkin Concert Hall. Violinist Sherban Lupu and pianist Ilinca Dumitrescu will also play several other Enescu pieces I would relish the chance to hear live, including the suite Impressions d’enfance (1940).

| Available from Amazon: George Enescu, Octet, op. 7 (1900), and Quintet, op. 29 (1940), Gidon Kremer, Kremerata Baltica, released May 21, 2002 |

George Enescu, Oedipe, Jose van Dam, Barbara Hendricks, Orchestre Philharmonique de Monte-Carlo, EMI, 1994 |

Charles T. Downey, Bach's Unaccompanied Violin Bible (November 17, 2005) Charles T. Downey, Kremerata Baltica at Shriver Hall (May 3, 2005) Jens F. Laurson, Kremerland (April 30, 2005) |

What seemed like an interior pulse of anxiety in the first movement (Très modéré) becomes overwrought in the second (Très fougueux), inviting some daring playing from Kremerata Baltica. The massive chords that introduce the concluding, accelerated section almost have an organ's timber in the amount of ring produced. That thrilling sonic climax winds down to a gentle conclusion, leading into the muted third movement (Lentement). The first two minutes of this movement, wheezing away sweetly, are captivating as rendered so simply in this performance. In the last minute or so, Enescu picks up the tempo, transitioning to the return of the main cyclical theme at the opening of the fourth movement. The themes of the movement pile up in a frenetic conclusion that rattles ineluctably to its end.

This CD was the first-ever recording of Enescu's more mature piano quintet, op. 29, from 1940. The more obvious folk references of the earlier Enescu works, like the third violin sonata, are gone by this point in his career. The first movement (Con moto molto moderato) is a suave and reserved diptych of two sections, with little of the wild drive of the octet. The second movement is faster in tempo but maintains the calm, smooth character of this enigmatic piece, composed during a very troubled period of history. I think this recording bears up quite well under repeated listening, which is exactly what it has been receiving from me this week, and is a good introduction to two facets of Enescu's compositional style and to the marvelous work of Gidon Kremer and his young musicians.

What may be Enescu's greatest masterpiece, his opera Oedipe (1936), received its American premiere only this year, by the Sinfonia da Camera Chamber Orchestra at the University of Illinois, on October 15. As I pointed out last year, this opera was also mounted at the Vienna Staatsoper last April. The EMI recording is certainly worth a listen.

After spending much of his adult life in France, Enescu was buried in the Père Lachaise cemetery. On visits there, I have often seen fresh flowers left by admirers on his grave, not to the same extent as Chopin's grave, of course, but still impressive.

6 comments:

We New Yorkers recently had the joy of hearing one of Enescu's star pupils, Uto Ughi. Thanks for the wonderful post.

VF, thanks for the kind comment and the reminder about your post on Uto Ughi. Bisous!

Thanks for the fine, short Enescu tribute, Charles. I saw the same Wien Opera production of "Oedipe", in Berlin, five years ago; and I subsequently pleaded with conductor Lawrence Foster to try to bring the work to the MET.

I was also fortunate to examine part of the score to "Oedipe" at the lovely Enescu Museum in Bucharest a few years back; as well as to visit two of the villas where Enescu composed in Romania --in royal Sinaia and in a then up-scale Carpathian resort town between Cluj and Suceava, whose

name now escapes me and which I can't quickly find on the Web.

(Uto Ughi give a sublime rendition of the Bach Chaconne at the LC several years back.)

up-scale Carpathian resort town between Cluj and Suceava

Vatra Donai... how could I have forgotten this Austro-Hungarian Carpathian watering hole ...

The scene with the Sphinx in the EMI recording is about as weird and chilling as you could wish for in opera. (What's the CD equivalent for "vinyl theater"?) The 1st Rhapsody might be a warhorse, but I read that Enescu transcribed it for piano. I'd love to hear that some time. Thanks for the posting. The Kremerata Baltica recording is on my list now.

Thanks for doing this. During the past year, I've spent a lot of time listening to recordings of Enescu's major works. The experience has convinced me that he is the most underrated composer of the twentieth century, perhaps all time.

Post a Comment