Kurt Masur Obituary & Discography

Kurt Masur died six years ago today, aged 88. He was born in Lower Silesia and after the war, into which he was drafted at 17, he moved to Leipzig to study conducting. That is the town in which, after short stations in Halle, Schwerin (State Theaters), Erfurt, Dresden (Philharmonic Orchestra), and Berlin (Komische Oper), he rose to musical fame as the Kapellmeister of the Gewandhaus Orchestra, starting in 1970. After he barely survived a car crash in 1972, in which his first wife died (the incidence was alleged to have been hushed-up), he stopped using a baton. With almost a thousand concerts given abroad, he was not just a cultural ambassador for the German Democratic Republic, but also one of its more important foreign currency cash-cows. He was at best politically disinterested and certainly outwardly loyal to the regime which allowed him a privileged life in the GDR. Well-meaning commentators suggest that he simply used his influence with the party to get money and then a new concert hall for his orchestra. Then Criminal-in-Chief Erich Honecker obliged and, although the country could not afford it, had the third—still superb—Gewandhaus orchestra hall built in time for the 200th anniversary of the orchestra first moving into the original Gewandhaus. Critics accused Masur of being a little on the effusive side, when he greeted and thanked Honecker at the opening of the hall on October 8th, 1981.

Kurt Masur was huge, towered over his orchestra at 6' 5", but had soft gestures, which made for an intriguing contrast… as it did to his sometimes brusque demeanor towards orchestra members. The tower started to slope and droop with age. The left hand became limp, and just twitched along with the music. The right hand would eventually be jittery, and long before Kurt Masur publically admitted, in October of 2012, to be suffering from Parkinson’s disease, the disease betrayed him and his music-making. There was a sense of him being trotted around on the concert circuit, despite diminishing musical returns, which was sad. Then again, he could still draw crowds, and musicians who knew him suggested that music was the only thing that kept him going. From that point of view—that of a life-prolonging measure—he had most certainly earned himself the right to continue conducting. Masur even said himself: “What should I do? Just quit conducting and wait for death?“

In Leipzig he hurtled towards fame beyond his musical acclaim, with his call for prudence on October 9th, which was promulgated through leaflets and a short speech broadcast on radio. His moral authority was attested to have helped to keep the gatherings, which eventually led to the fall of the GDR’s regime, peaceful. Suddenly Kurt Masur was the conductor of German unification. The New York Times stylized him a “cousin of Martin Luther”; some locals wanted him nominated for the Nobel Peace prize, and politicians approached him to stand for the (largely representational) role of German President. He opted to become the music director of the New York Philharmonic, instead.

The New York Philharmonic wasn’t in good shape after neither Pierre Boulez nor Zubin Mehta were able to counter the slump into which the orchestra fell after its long Bernstein-high. There was a fear that “Leipzig-on-the-Hudson could be a duller town than Mehtaville” (Donal Henahan). Masur might not have made the New York Philharmonic an interesting orchestra, but he made them better.

In 2000, Serge Donier asked him to be the principal conductor of the London Philharmonic Orchestra, to steer the orchestra into save waters while they looked, without hurry, for a new conductor of the next generation for the LPO. (It turned out to be very successful Vladimir Jurowski.) In 2002 he became the music director of the Orchestre National de France; a post which he held until 2008 (to be succeeded by Daniele Gatti).

The Masurine conversion from regime-benefactor to regime critic and hero of peaceful regime change meanwhile, was a very, very late one. The ascent to hero-of-the-free-people did not sit well with everyone who knew him from the years before. In my attempt to follow up on hints and suggestions of discontent, I approached the Gewandhaus Orchestra to speak to players who had worked with Masur. Without exception, they all refused to speak their mind about Masur, as it would not be proper, so soon after his death. A non-statement about as telling as any statement could have been.

But Masur is not just controversy.

The Ten Best Recordings of Kurt Masur

Granted, when I went to think about the great Kurt Masur records that will remain with us and give testimony to his art, I drew a blank at first. “Solid” just rarely translates into lasting greatness on record (certainly not from that period with the comatose New York Philharmonic). And many of Masur’s discographic achievements, while lauded and important at the time, have slipped out of print and out of collectors’ consciousness. His conducting, I found, offered no more, if rarely less, than earthy, solid, craftsman-like results. Still, there are some real gems and they are decidedly worth exploring.

He recorded two cycles of Beethoven Symphonies, for example, both with the Leipzig Gewandhaus. One between 1972 and 1974, which Philips recorded in un-utilized quadrophonic sound. It was the premiere East German Beethoven on a Western label (though Herbert Kegel’s fine cycle on Capriccio should not be overlooked), but it was wedged out of the market on either side by Karajan’s first and second Berlin-cycles. When Pentatone re-issued the set, as-intended, on SACD, it greatly improved the sonic experience but unfortunately not the steady, unflappable, slightly stodgy interpretation. The second cycle, shortly after unification, flopped on arrival, though that was largely due to marketing inaptitude or lack of fortitude: Most people didn’t notice that a set of Beethoven symphonies with Masur had indeed been issued, and of those who did, many assumed it was just a re-issue of the earlier set.

ArkivMusic lists 259 available recordings with Masur conducting, but the majority of them are inclusions in the kind of compilations into which middle-of-the-road performances get drafted and where anonymity is no sin. Perhaps it is telling that the great recordings of Masur that come to my mind have him in the rôle of giving orchestral support to a soloist: He knows how to operate in the background without ostentatious attempts to make it about himself. Surely an art, and one worth being remembered for.

|

Brahms, Violin Concerto, Mutter, NYPhil, DG

On paper, I will concede, this was always a recording that didn’t appeal to me in the least; a potential trifecta of tedium. How wrong I was: This is an unbelievable recording; a white-hot must-have. There exists a rumor that days before this live performance, Mutter’s first husband died. Se non è vero, è ben trovato; said husband died almost two years earlier. But the recording is dedicated to his memory. And whatever the reason, the planets seem to have aligned for this one in some special way: there’s no fiercer, searing, determinate account of this concerto on record. It’s not the only way to play Brahms, of course, but it’s the most sizzling way to do so.

|

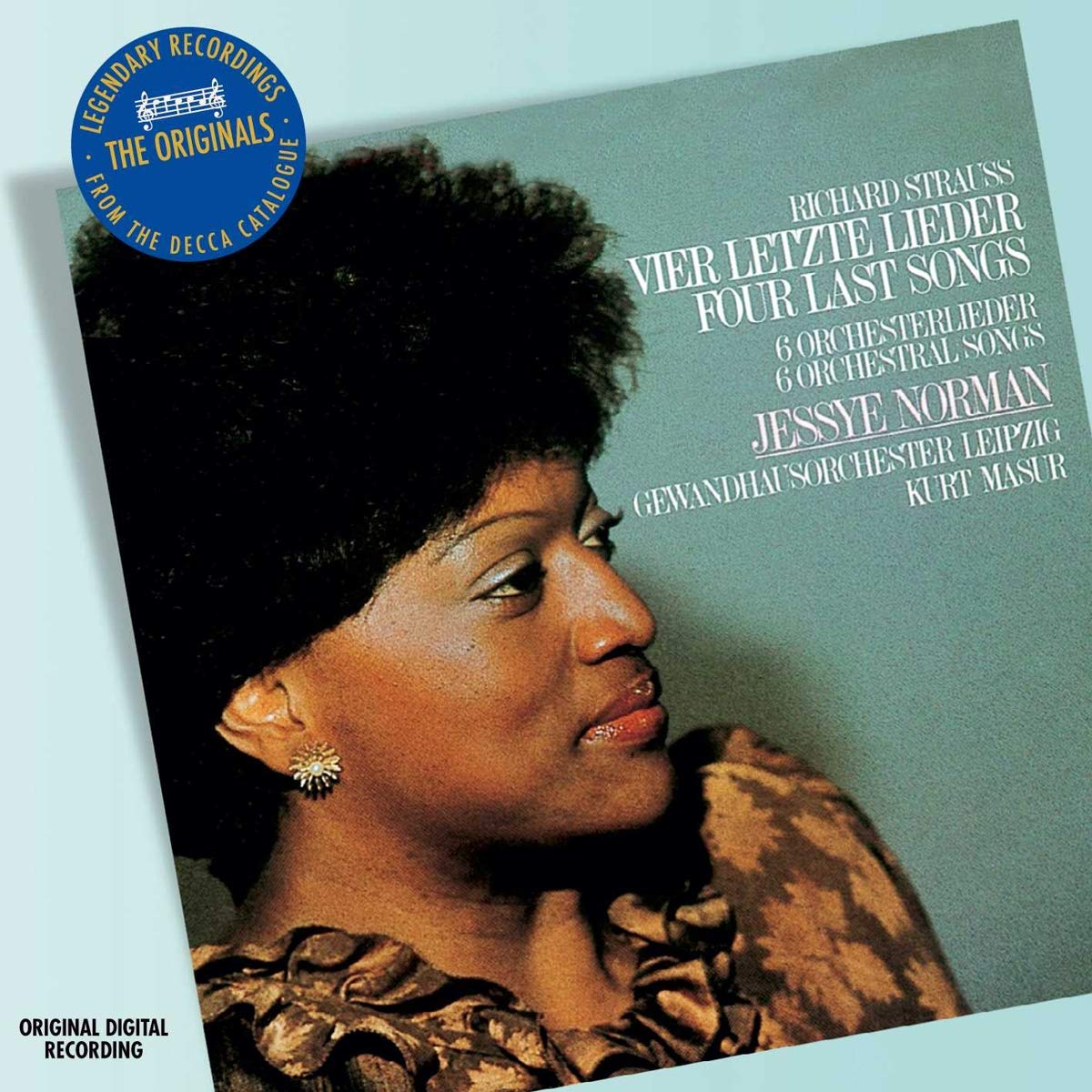

Strauss, Vier letzte Lieder, Norman, Gewandhaus Orchestra, Philips/Decca

If I were to put together a bundle of CDs to introduce and captivate a classical neophyte, this one would be among them. In fact, it is! The double-cream gorgeousness of Jessye Norman in the equally sumptuous, lavish Four Last Songs of Richard Strauss’ is superbly embedded by Kurt Masur and the Gewandhaus Orchestra, who coax the maximum of slowness out of the music. (Masur also provides excellent musical bedding for Deborah Voigt in her recording of the Four Last Songs with the New York Philharmonic on Teldec, but it’s not quite as outrageously beautiful as the Leipzig rendering.)

|

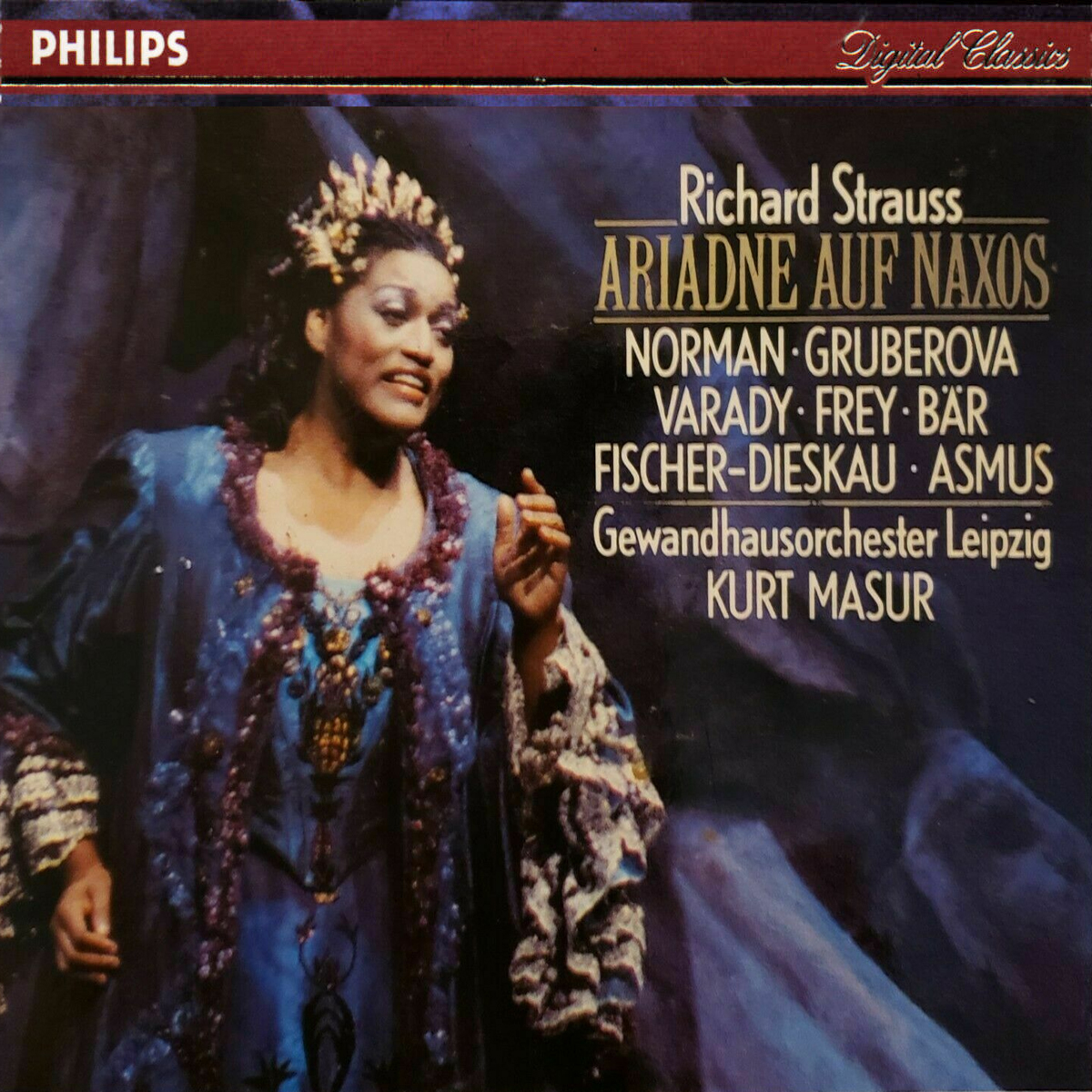

Ariadne auf Naxos, Norman, Gewandhaus Orchestra, Philips/Decca

With a sultry Jessye Norman, an Edita Gruberova (RIP) at her coloratura-best, the fresh Olaf Bär, accurate-didactic Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau alongside Julia Varády and the best (surprisingly lean) of Leipzig’s orchestral accompaniment: This Ariadne auf Naxos is top notch stuff and a personal favorite alongside its southern, slightly more modern rival from Dresden with Giuseppe Sinopoli.

|

Shostakovich, Violin Concertos, Sergey Khachatryan, ONdFrance, naïve

This is a first rate recording in every way, and one that helped catapult violinist Sergey Khachatryan to his very considerable career. Heaving and sorrowful and jaunty and overjoyed in turns, Khachatryan benefits from the sensitive and flexible playing that the Orchestre National de France provides under Masur who, in 2006, mustered his powers for a later winner.

|

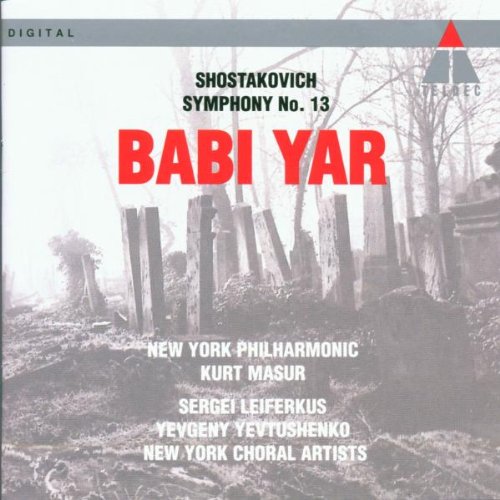

Shostakovich, Symphony No.13 “Babi Yar”, NYPhil, Teldec

Masur picked his Shostakovich carefully, it seemed, and what he recorded of the composer was always above average. The aforementioned concertos, an underplayed but very decent Seventh from New York, a weighty and slow-burn Fifth with the LPO, and this “Babi Yar”, also with the New York Philharmonic, which is one of the strongest in the symphony’s discography and one of the happiest examples of the Masur-Big Apple connection on record. Despite that, it is probably Sergei Leiferkus who is the star here, giving the most haunting performance of the Yevtushenko poem since Vitaly Gromadsky sang the unadulterated version under Kiril Kondrashin (Praga Digitals).

|

|

Bruch Violin Concertos & Symphonies, Accardo, Gewandhaus Orchestra, Philips/Decca

Bruch was disheartened that his smash-hit First Violin Concerto, even in his time, overshadowed the rest of his output. Tastes had moved on and left worthy composers in the cold before they said however much they still had to say and however much worth hearing it was. By enjoying Bruch’s Violin Concerto No.1 today, we show that we appreciate greatness in music across times and irrelevant of concurrent styles. But by ignoring his other two subsequent violin concertos we show that we are still victims of prevalent moods from a century ago. Let’s not. Although Nos. Two and Three are out-recorded roughly 10-to-1, they are both very fine works which Bruch, understandably, deemed as good or better. At worst, they are not as original, but only because they came later. Amazingly enough, Salvatore Accardo and Kurt Masur’s is still the only recording dedicated to all three concertos. It’s a searing, dark-chocolatey-romantic affair from First to Third and perhaps its superb quality has scared imitators off. The same, more or less, goes for Bruch’s Three symphonies and Masur’s recordings thereof, so pick those up along the way.

|

|

Beethoven, Complete Overtures, Gewandhaus Orchestra, Philips / Pentatone

There’s less competition in this field, than with Beethoven symphonies, which helps. And Masur’s overtures are steadily excellent, which also helps. He isn’t out for easy highlights, brash fortissimos, or obvious climaxes: it’s the solid, sturdy path to those culminating points that Masur pays most attention to. Because overtures are shorter, there’s less a chance of boredom to set in along that way, and the craftsmanship can be more easily admired, especially in the great-sounding remastered re-release on two Pentatone SACDs.

|

Dvorák, Violin Concerto, Maxim Vengerov, NYPil, Teldec

The Dvorák Violin Concerto is slowly gaining in deserved appreciation. So slowly, you would think there must be something wrong with it, when such a famous and beloved composer’s work in such a popular genre is being de facto ignored. But there isn’t, except for the fact that there aren’t that many great recordings. Mutter/Honeck (DG) may be the modern standard, and Tetzlaff/Storgårds (Ondine) and Steinbacher/Janowski (Pentatone) fabulous rivals. But for many years, Vengerov and Masur had set the standard, and their interpretation – an excellent mix of the tenacious (Vengerov) and the luscious (Masur) – makes it stand right in line with the two late symphonies. It has lost little to nothing of its lavish standing.

Schubert/Liszt, Wanderer Fantasy “Concerto”, Symphonies 3 & 8, Boris Berezovsky, NYPhil, Teldec

This disc is noteworthy not for the Schubert symphonies (a fine, but not light or particularly sunny third; a Mendelssohnesque, crepuscular Eighth) but for Liszt’s orchestration of Schubert’s Wanderer Fantasy, who thus turned the solo piano piece it into a strange early-yet-late romantic piano concerto—unknown and yet we can whistle along to it. There aren’t many recordings of it out there and taking sound quality into consideration (which rules out Clifford Curzon with Henry Wood), this tops the list ahead of himself with Michel Béroff (EMI) and perhaps even Bolet/Solti (Decca). It’s disconcerting how eerily well the orchestration works. One could swear that one has heard it before and never as something other than an orchestral piece. Incidentally ideal to stump even the most expert musical friends after dinner.

|

Mahler, Symphony No.9, NYPil, Teldec

The Ninth brings out the best of many conductors in Mahler, and Masur is no different. This one stands out among Masur’s Mahler at least, if not all Mahler Nines. The sonics are great and the New York Phil of that time sounds pretty darn good for once. Ančerl it ain’t, but then no one else is, either, and it brings weight, unfussiness, and great sound to the table. Terrific third movement, certainly. Anyway, good enough to make it a full ten recordings, as lists like to come in tens. Other suggestions? Furious about omissions? Apoplectic for what I have picked? Abuse me on Twitter for some fun back and forth.

Follow @ClassicalCritic on Twitter