The issue of performer-and-hair has recently come up on a conversation thread on the instagram account of the fellow writer, obsessed listener, and musical explorer "foreignwords" (he runs the podcast & website Fugue for Thought). There, the cellist Carmine Miranda, having just joined the social media world, found a mention of himself regarding his recording of the Dvořák and Schumann cello concertos which he took exception to. I had made the particular comment and was briefly the subject of the artist’s vented ire. (We've since made up.)

The ionarts Hair-RADAR

Hair is a hairy issue and has a particular, if minor, place in classical music. Beethoven’s revolutionary mane seems almost the embodiment of his music and personality, in a time of manicured wigs. Haydn was expelled from the choir he served in—if memory of the Haydn-for-Kids tape I used to devour as a tot serves me correctly—for clipping his fellow chorister’s wig’s pigtail. There has been a harpsichordist’s spat recently, and at the root of it hair. And when we imagine Bach, it’s the wig that comes to mind first.

Hair has made its appearances in several of my ionarts reviews, too. I’ve just (re) published the interview with Daniel Müller-Schott, whose pony-tail had for the longest time given me a negative bias which I, in order to do his art any justice when I ran into it, had to consciously overcome. (His hair is absolutely impeccable now.)

On cellist Alban Gerhard: “. It is difficult to align [Alban Gerhardt’s] youthful good looks with the fact that he already looks back on an illustrious 15-year career in Europe. Although that hair is just two years from being designated a comb-over…” (Dohnanyi's Brahms Wins the Day).

On cellist/conductor Michael Sanderling: “…Attendance would be seemly for the following reasons, in order: […] #3: Here I was going to list Michael Sanderling’s hair (see: Sanderling Jr. for Muti), which is the only legitimate successor to Riccardo Muti’s. But Sanderling, the youngest of the conducting clan, had to cancel the tour.” (National Youth Orchestra of Germany rocks Viktor Ullmann)

On Heinz Holliger: “Heinz Holliger is wonderful: A charming advocate of contemporary music—his own but especially that of others’. Still an outstanding oboist. The finest Haydn conductor I’ve heard in concert. And of course someone who has taken the comb-over to Olympic levels… often going with “Squirrel-that-came-home-to-die”, or another successful creation that he sported on this occasion of the Klangforum Wien performing contemporary Japanese composers: the “Pigeon-that-flew-into-a-ceiling-fan”; a lighter, fluffier creation particularly suited to hot Salzburg summers.” (Notes from the 2013 Salzburg Festival ( 16 ) | Salzburg contemporary • Klangforum Wien 2, Heinz Holliger)

I’ve not found mention of it on ionarts, but I’ve long suspected Gautier Capuçon of being more concerned about his hair than his intonation and a generally lesser musician than his clean-cut brother. Even though my first impression of him in concert had been a very positive one. (Also I’m beginning to notice: What’s with cellists in particularly featuring so prominently on my hair-radar? Notes for the couch.)

The Bone of Contention

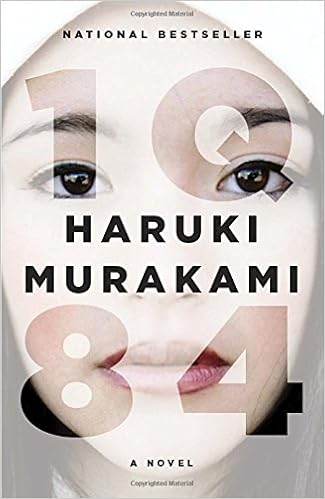

Foreignwords’ posted the CD cover of Carmine Miranda’s recording (and a generous remark about the recording’s quality). My comment on it ran thus: “I reject this performance on ground of its hair. (Tell me that I really need to put this back out of the discard bin...?!?)” A mixture—less obviously than I had thought—of snark and poking fun at my own biases.

Schumann & Dvořák, Cello Concertos

Carmine Miranda, Moravian PO, P.Vronský

Navona (Parma) Recordings

|

This, as you might be able to imagine, did not please the artist: “Since I am brand new to @instagram and trying to figure things out” he wrote, “I came across this very ignorant reply. I understand that this post is quite a few months old but I couldn't resist to reply to this myself…” And off he went. On his own account, he posted a screen shot, circling the offending passage, and continued: “Can you believe this guy? (@classicalcritic) He definitely puts a new meaning to "listening with your eyes". He is a "classical #music #critic" for the acclaimed #classical #publication @listenmusicmag and @Forbes. His premise for not #listening or even reviewing my latest recording of the Schumann and Dvorak #Cello Concerti is because he doesn't like my hair? I hope this is not a representation of the magazine that I have been reading since I was a child…”

I could dissect the statement (especially on this poor child of my imagining having to read Forbes magazine as a toddler), but that is tit-for-tat nonsense and would only be good for imaginary score-keeping and playing to the peanut gallery. The kerfuffle seemed mostly a slew of misunderstandings and perhaps a touch of bent ego. Mr. Miranda[1] might have thought that I dismissed his performance because of his Off-Off-Broadway-Pirates-of-the-Caribbean-the-Musical looks[2]. [I have since heard from him in a message[3] that shows that it is possible, with a bit of mutual effort, to take a social-media tussle and turn it into something productive, creative.] But I hadn’t taken a dislike to his interpretation based on such a ludicrously superficial reason as his looks[4]. Much rather I had simply not given it a first chance. Still, he does get it partly right in his second statement: “Can you believe this guy? […] His premise for not #listening or even reviewing my latest recording of the Schumann and Dvorak #Cello Concerti is because he doesn't like my hair? […] You can't please them all, especially the #ignorant! I bet he didn't see this one coming! #unbelievable”

Listening-Choices: Soft and Hard Biases

If this is a bit humorless, as far as responses go, it’s because he is missing a crucial element in which—in a self-referential way—am poking fun at that dismissal because it is/should be obviously ludicrous and unrelated to the performance. That could be overlooked… And I have often noticed with myself that my sense of humor tends to make a hasty retreat whenever the target of a joke or criticism is my own person, leaving only flustered outrage at the front to deliver the response. It’s also a clumsy response, because it stokes potential antagonism, rather than trying to sooth it. But that, too, is understandable. Especially in the semi-anonymity of the internet.

The real disconnect lies here: Carmine Miranda thinks that I obviously, decidedly should listen to his recording. (Fair enough, from his point of view.) When he reads the hair-nonsense, he must think: “This guy had the choice between listening to my recording and not listening to it… and he didn’t listen to it for that of all reasons?”

That would be potentially upsetting, but it’s not so. In reality my choice is whether I should be listening to this, or this, or this, or this [etc. ad infinitum] recording. And his CD is somewhere among the stacks of hundreds of CDs I still have to make my way through. I have to be discriminating, somehow, unless I grab randomly into the To-Be-Listened-To shelf or boxes. Quite naturally I am led by all my biases in choosing which recordings I will listen to first. These biases are manifold and wide-ranging and—as is the nature of biases—wildly subjective: The composers I like and what time of the day it is. (Weinberg in the morning isn't as attractive as Thomas Tallis; Casella in the evening with a bottle of Birrificio Via Emilia, but not Ferneyhough…) Or my opinion of the label. The quality of the presentation or even the quality of the jewel case. The professionalism of the design or the font-choice. What I have listened to the day before. Whether I have heard of the artist. How does she or he present her- or himself? And here we are in that territory where hair enters again.

These are soft biases; they can push a recording to the front or the back of the considerable listening-pile. (There are a few hard biases, too: Anything by John Rutter is out, as would be Riccardo Muti conducting Schubert. Bach, Haydn and Alexandre Tharaud are always in. But that’s really it.) A haircut could be said to be a simply superficial way of making such a choice. Silly, and besides-the-point, but not really worse than many other reasons.

Then again a haircut could also be considered an initial communication on the part of the artist. Especially on a cover photo. An artist’s choice of dress or undress, coiffure, or makeup is one of the ways in which an artist wants to communicate[5]. Fusty writers complain when comments are being made regarding the state of dress of the likes of Yuja Wang et al. (see also: A Yuja Wang Dress Report, Prokofiev 2, and the Munich Philharmonic in Brahms), but this is rubbish. Thought gets put into dress and presentation and to suggest that they don’t matter at all would be as silly as suggesting that the presentation of food in a restaurant doesn’t matter. Worse: It’s a case of lying to oneself or just a dismal lack of awareness of one’s own biases. And that’s one of the points I wanted to arrive at: It is better to be aware of one’s biases than to be ignorant about them. Speaking about them in public is not only OK, it should be encouraged. Outward appearances influence our judgement. If we are not afforded to be blind, we must be aware[6]. Acknowledging them—and certainly making fun of them—is not the same thing as being proud of them (which would be worrisome). Being aware of our (and others’) biases helps us, when called upon, to try our best to overcome or avoid them. In order to give criticism of any kind any validity, we should be aware of them constantly and try to overcome them or else state them bluntly (which is also useful).

For any artist, this might be helpful to understand. There is often reason or awareness behind that which may seem outrageous to quickly offended sensibilities. If one puts all of oneself into a project, an interpretation, then rejection of any kind—especially the inconsiderate kind—must sting because it is in essence a rejection of the person they are. But that’s the artist’s life and those who learn not to care too much, or to take everything with a grain of salt will fare better. A slight sense of detachment helps, a dose of irony or self-deprecation can break the ice. It would have been easier for everyone, had Carmine Miranda responded by saying “I reject this critic’s opinions on grounds of his shoe size” than if he had tried to make an exasperated example of my alleged ignorance. No one likes a thin-skinned artist; everyone loves someone displaying a sense of humor in a tough spot. Still, we’ve managed to find common ground quickly enough and he’s got his way and I my benefit: He’s got me listening to his recording now, and more intently than I might otherwise had and I’ll learn something. But just to get around my biases, I shall make it a blind listening, instructing a friendly helper to mix a few interpretations and play them to me. It’s the thing you do when you fear that you might otherwise reject a performance on account of its [sic] hair. After that, I hope, Carmine Miranda and I will continue the conversation about Schumann and superficial perceptions.

[1]

[1] He first responded to my suggesting that this was less reason to take offence than a misunderstanding by offering that I may ‘reach out to [him] through [

his website] if I would like to learn more about his performance, interpretative choices and [were willing to] give the recording a second chance’. Nice and all, but still reversing the ‘duty of interest’…. “Duty of interest” meaning that I have no inherent duty or inclination to be interested in anyone’s work – whereas an artist’s work has the duty (or intent, certainly) of

making me interested in it.

[2] Incidentally: I had the CD lying around as an acquaintance stopped by last night and the cover prompted an immediate, unsolicited comment of rather unflattering nature. Arguably it’s only natural that my realm of acquaintances may, on average, tend towards a similar ideal of kemptness [sic] and self-presentation. But I think the take-away is: The cover does and will, objectively, divide opinions quite strongly.

[3] “Very nice! I’ll tell you what! Why don’t we turn this into an informational and educative experience for both of us and readers? I am willing to personally send you a copy of this record and a full copy of my scholarly research (Musical Times Journal of Music, London) on “Decoding the Schumann Cello Concerto” which was the basis for my interpretation of one of the concerti (very briefly summarized in the liner notes). If you are willing to put aside your bias and give it a “first listen” we can discuss about your views and mine, interpretative choices, questions you might have about the album or even listening gear (e.g. why did you prefer this instead of that?) openly and publicly.”

[4] Looks which I had in any case attributed to the

performance itself, which I thought would have made the coy absurdity of the statement more pointed.

[5] Unless he or she just doesn't care at all – and even then not caring about one’s appearance—Holliger, Sokolov—is also a statement!

[6] (Does no one remember Kurusawa’s

Sanjuro, which takes up that issue?)