Shaken by criticism of his epic poem Maud, which was published in the same book as the Charge in 1855, Tennyson proposed removing almost half the famous account of the Crimean war tragedy. Among lines struck out in black ink in the poet's firm hand were "Theirs not to reason why/Theirs but to do and die" and "Someone had blunder'd". Tennyson, who was so mocked by critics as a young writer that he published no poetry for nine years, wrote "Here comes the new poem" on the proofs, which he instructed his publishers to burn. He was notoriously unwilling to let people see his revisions, and the annotated copy is the only one known.The book, which belonged to American collector Halsted Billings Vander Pole, will be auctioned at Christie's in London next month. If you want a real trip, listen to this amazing wax recording of Tennyson himself reading the Charge of the Light Brigade (from The Tennyson Page). Dante Gabriel Rossetti's sketch of Tennyson reading his epic poem "Maud," from around this time and shown here, also comes from The Tennyson Page. I'm sure that this is a rare example of the power of reviewers, but it is a good thing to remember that a critic may have prevented a line like "Theirs not to reason why/Theirs but to do and die" from being published.

31.1.04

The Pernicious Influence of the Critic

30.1.04

Brassaï

"Night suggests, but it does not show. It frees the forces in us that, during the day, are subdued by reason." He loved the faces that tell a story, the little jobs that speak of the town's real nature, the places of pleasure, the reverberations, and their spots of light. Let's go! On his back, twenty-four unexposed plates (the maximum he could carry) and his camera (rather unwieldy, like those of the time [see the self-portrait Brassaï, Boulevard Saint-Jacques, 1932]). The stroll begins.There are lots of images of Brassaï's photographs to see online, including the Brassaï pages from Masters of Photography; Brassaï and Night Photographs from Boston University; Brassaï: The Soul of Paris (2001) at the Hayward Gallery in London; Brassaï: Das Auge von Paris from the Kunstmuseum in Wolfsburg; and, with no images, an interesting article about Brassaï's reading of Proust (Brassaï, lecteur de Proust, by Jean-Pierre Montier).

In 1932, his first book appeared: Paris by Night, sixty-two images with a preface by Paul Morand. A triumph at the bookstores. This poetry without sentimentality, this intoxicating seizure of contrasts, this shimmer of lines, yes, Paris recognized itself in his work, and his friend Henry Miller gave him the title of "the eye of Paris." André Breton wanted to bring him into his surrealist group, but he always resisted, suspecting Breton to be a tyrant and accepting only the presitigious collaboration on the Minotaure review, where his spread showed magnificent nudes [see these two examples]. "They thought of my photos as surrealist because they revealed a ghostly Paris, unreal, drowned in night and fog. But the surrealism of my images was nothing but reality rendered fantastic by dreaming. I sought only to express reality, because nothing is more surreal."

What the Eye of Paris recorded is not only the beautiful and serene (for example, The Viaduc d'Auteuil at Night, 1932; and Matisse Sketching, 1939) but scenes from the underworld of 1930s Paris: prostitutes (Chez 'Suzy', 1932; Prostitute at Corner of Rue de la Reynie and Rue Quincampoix, 1933), old frauds (Bijou, 1932), drug users (Opium Den, 1931), the homeless (Clochard Looking for Food, 1932), homosexuals (Lesbian Couple at Le Monocle, 1932), or street thugs (Toughs in Big Albert's Gang, 1931-32). Think of Brassaï's photographs as the visual counterpart to a book like Henry Miller's Tropic of Cancer.

29.1.04

Snow Art — by Mark Barry

I’d much rather be thinking of paintings with a warm climate theme—think Paul Gauguin; however, you have to deal with what is before your eyes. A beautiful white carpet of snow has been covering the mid-Atlantic region and I have been inspired. Maligned by commuters, romanticized by lovers and musicians, thrilling sledders and snow angel enthuthiasts, snow leaves an indelible impression.

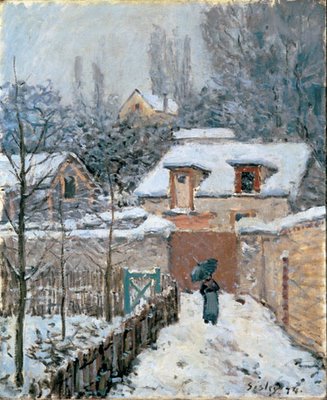

Looking out my studio window, maybe too much this past week, I love how the stark winter trees cast long shadows of purple and blue across the white snow pack. Nature is rarely this graphic: an opportunity for some very straightforward imagery. Think Alfred Sisley (Snow at Louveciennes, 1875, Musée d'Orsay, shown at left; or Road under Snow, Louveciennes, c. 1876, Private Collection), Claude Monet (The Cart; Snow-Covered Road at Honfleur, with Saint-Simeon Farm, c. 1867, Musée d'Orsay), or Pieter Bruegel the Elder (detail from The Hunters in the Snow (January), 1565, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna), a favorite of mine: these are not paintings made gazing out the window of a warm studio, they are easel stuck in a snowbank, frozen palette paintings, the original arctic explorers.

Several years back The Phillips Collection had a fabulous exhibit of snow paintings (Impressionists in Winter: Effets de Neige, 1998; and at the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts in San Francisco in 1999). It was a gem of a show that is still talked about to this day, a refreshing look at snow through artists' eyes, and there were many. (See also the selection of snow paintings from the BBC online exhibit Painting the Weather.)

So let it snow, let it snow. Enjoy, it’s a gift.

Mark Barry (www.markbarryportfolio.com) is an artist working in Baltimore.

Looking out my studio window, maybe too much this past week, I love how the stark winter trees cast long shadows of purple and blue across the white snow pack. Nature is rarely this graphic: an opportunity for some very straightforward imagery. Think Alfred Sisley (Snow at Louveciennes, 1875, Musée d'Orsay, shown at left; or Road under Snow, Louveciennes, c. 1876, Private Collection), Claude Monet (The Cart; Snow-Covered Road at Honfleur, with Saint-Simeon Farm, c. 1867, Musée d'Orsay), or Pieter Bruegel the Elder (detail from The Hunters in the Snow (January), 1565, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna), a favorite of mine: these are not paintings made gazing out the window of a warm studio, they are easel stuck in a snowbank, frozen palette paintings, the original arctic explorers.

Several years back The Phillips Collection had a fabulous exhibit of snow paintings (Impressionists in Winter: Effets de Neige, 1998; and at the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts in San Francisco in 1999). It was a gem of a show that is still talked about to this day, a refreshing look at snow through artists' eyes, and there were many. (See also the selection of snow paintings from the BBC online exhibit Painting the Weather.)

So let it snow, let it snow. Enjoy, it’s a gift.

Mark Barry (www.markbarryportfolio.com) is an artist working in Baltimore.

28.1.04

Delacroix in Karlsruhe (as seen from snowbound Washington)

If one snow day is good, three snow days are even better. We are on Day 3 of the annual winter disaster in Washington, and there has been no school since last Friday. Far be it from me to complain about getting too many days off because of a little snow and ice, but last year we had so many that we lost part of our spring break.

Jean Pierrard's little article (Sang pour sang Delacroix, January 9) in Le Point is an appreciation of an exhibition of the works of Eugène Delacroix at the Staatliche Kunsthalle in Karlsruhe, Germany, which will end on February 1. (You can read the Web site for the show, Eugène Delacroix, in German or French, but not in English.) According to Pierrard, the selection of more than 200 paintings, watercolors, drawings, and engravings reveals a dark but edifying Delacroix:

Jean Pierrard's little article (Sang pour sang Delacroix, January 9) in Le Point is an appreciation of an exhibition of the works of Eugène Delacroix at the Staatliche Kunsthalle in Karlsruhe, Germany, which will end on February 1. (You can read the Web site for the show, Eugène Delacroix, in German or French, but not in English.) According to Pierrard, the selection of more than 200 paintings, watercolors, drawings, and engravings reveals a dark but edifying Delacroix:

"Lac de sang hanté des mauvais anges" [Lake of blood, haunted by the fallen angels], as Baudelaire saw it so well. Messy assassinations, large-scale abductions, shipwrecks, a persistent anguish. Glorious corpses between dust and flags and others, more interesting, drawn from mythology under the heading of crimes of passion, like Medea stabbing her children. As shown by the impeccable retrospective exhibit of the Karlsruhe museum, the work of Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863) reads like the darkest of crime novels.The opening of the article refers to Charles Baudelaire's essay on Delacroix, written in response to seeing his paintings at the 1855 Universal Exhibition. The line of poetry was quoted by Baudelaire in the essay from his own poem Les phares (in English, The Beacons), published in his collection Les fleurs du mal (in English, The Flowers of Evil). The Medea painting Pierrard mentions (Médée sur le point de tuer ses enfants [Medea about to kill her children]) was begun by Delacroix in 1838 and not finished until just before he died in 1862. It is now in the Louvre and is indeed a dark painting on the horrifying subject of infanticide.

The monster of pride in a strangling tie whom we make out in daguerrotypes of 10 square cm [1.5 square inches], the dandy with narrow shoulders petting his cat in the comfort of his studio was a man with a single obsession: death. He whom Cézanne credited with the most beautiful palette of French painters adored cadavers. The macabre was part of his preferred medium. Was he terminally shaken by the news of the death of his older brother, Henri, killed in Friedland in 1807? Was his childlilke sensibility shocked too often by the Te Deum which, with great ringing of bells, regularly called the populace to celebrate the Corsican ogre's latest victory? As soon as he could, Delacroix painted the unspeakable: a soldier stretched out ingloriously between two dead horses on a battlefield abandonned by Marshal Marmont. To better understand the simultaneously tragic and banal character of this scene, Delacroix even went to the place in 1824 with two of his friends.I would love to link you to an image of this work, but I have yet to identify it.

The following year, it was with a picturesque touch that he reset the table, depicting a mortally wounded Mediterranean brigand [c. 1825], busy quenching his thirst in a stream, the ruffian's blood mingling with the mud. As connaisseurs of Romantic things, the Germans appreciated the Voyage d'hiver, a picture from the borders of despair, in which the colors sound the knell with as much conviction as in Schubert's darkest songs. Even women were not really able to distract the artist from these morbid tendencies. He was not attached to Aspasie [c. 1824], a mulatto woman who, at one time, was his model. He hardly came back to the nude, which he had once tasted with a salacious look, as shown by a splendid page from 1818 to 1820, rarely shown in public. From 1827, avoiding marriage and happy soon to be knocking up his maid, the future head of the Romantic School dreamed of odalisques, like this Femme au perroquet vert [Woman with green parrot, 1827], lolling about in a sultana's pose. Only the happy trip to Morocco in 1832 appeased the artist and freed him momentarily from his nightmares. The light, the colors of the countryside, the languid attitudes of a calm populace had a soothing effect on him. Of course, a lion escaped from a hunt bites from time to time, between two fantasias, an unfortunate wanderer in the bush [Cavalier arabe attaqué par un lion, 1849]. But, for the most part, Morocco inspired peaceful images to the creator of the Massacre of Chios. He was enchanted by the festivities of a Jewish wedding [Jewish Bride, 1832; or Saada, the Wife of Abraham Benchimol, and Préciada, One of Their Daughters, 1832], he noted with care the ritual accompanying the the Tournament of the Caïd [Moroccan Caid Visiting His Tribe, 1837], during which one extends a plate of milk as a sign of peace—so many images that will permit him later to evoke Morocco once more.You can see some Delacroix's sketches of Moroccan scenes taken from his journals.

Ten, twenty, or thirty years after his African expedition bursts of fire from the Moroccan paintings will rise up again. From the Marchand d'oranges [Orange merchant, 1852] to the Vue de Tanger prise de la côte [View of Tangiers taken from the coast, 1858], they appear like oases of tranquility amid a body of work often knotted up like a python in fury as one sees in the Louvre, on the ceiling of the Galerie d'Apollon [Apollo vanquishing the Python, 1850–1851]. And of which this exhibit offers the hallucinatory sketch.What I have tried to do here is reconstruct in images what is in this exhibit. Since many of them are from private collections, such a goal is ultimately impossible. Although you can also see fourteen images from the exhibit through the official Web site, I renew my call for museums to make more comprehensive online versions of their exhibits. Sadly, I am not likely to make it to Karlsruhe before Sunday.

27.1.04

Marcel the Judge

As you probably know, I have been reading Marcel Proust's À la recherche du temps perdu and, worse than that, subjecting the Ionarts faithful to posts about scenes and characters in the novel as I try to pick them apart in my mind. The book is a first-person narrative, meaning that the real subject is the author himself, or rather a somewhat dishonest transformation of him, since much of Proust's real experiences are embedded in other characters. In the fourth volume, Cities on the Plain (in French, much more evocatively, Sodome et Gomorrhe [Sodom and Gomorrha]), Proust lets us know quite explicitly that he knows the game he is playing, by fictionalizing his own life and the people he knew to make a book. Faced with the gift of manuscripts of three Ibsen plays, the Duc de Guermantes reveals his uneasiness about knowing authors:

A sort of cube with one side removed, so that the author may at once put inside it the people he meets. The narrator Marcel is indeed a shameless voyeur. The major revelation about the Baron de Charlus, mentioned toward the end of the third book but delayed until the opening of the fourth, is discovered quite randomly by Marcel. Standing on a stairway, he observes, unnoticed, the mutual identification of Charlus and the tailor Jupien, part of what is called "cruising" in our day. (At this point in the story, Proust was probably picturing the older, fatter Robert de Montesquiou, as shown in the sketch portrait by Jacques-Émile Blanche shown here. Thanks to Gabriella Alú's comprehensive and beautiful Marcel Proust site for the image.)

A sort of cube with one side removed, so that the author may at once put inside it the people he meets. The narrator Marcel is indeed a shameless voyeur. The major revelation about the Baron de Charlus, mentioned toward the end of the third book but delayed until the opening of the fourth, is discovered quite randomly by Marcel. Standing on a stairway, he observes, unnoticed, the mutual identification of Charlus and the tailor Jupien, part of what is called "cruising" in our day. (At this point in the story, Proust was probably picturing the older, fatter Robert de Montesquiou, as shown in the sketch portrait by Jacques-Émile Blanche shown here. Thanks to Gabriella Alú's comprehensive and beautiful Marcel Proust site for the image.)

| The Duc de Guermantes was not overpleased by these offers. Uncertain whether Ibsen or d'Annunzio were dead or alive, he could see in his mind's eye a tribe of authors, playwrights, coming to call upon his wife and putting her in their works. People in society are too apt to think of a book as a sort of cube one side of which has been removed, so that the author can at once 'put in' the people he meets. This is obviously disloyal, and authors are a pretty low class. Certainly, it would not be a bad thing to meet them once in a way, for thanks to them, when one reads a book or an article, one can 'read between the lines', 'unmask' the characters. After all, though, the wisest thing is to stick to dead authors. | Le duc de Guermantes n'était pas enchanté de ces offres. Incertain si Ibsen ou d'Annunzio étaient morts ou vivants, il voyait déjà des écrivains, des dramaturges allant faire visite à sa femme et la mettant dans leurs ouvrages. Les gens du monde se représentent volontiers les livres comme une espèce de cube dont une face est enlevée, si bien que l'auteur se dépêche de <<faire entrer>> dedans les personnes qu'il rencontre. C'est déloyal évidemment, et ce ne sont que des gens de peu. Certes, ce ne serait pas ennuyeux de les voir <<en passant>>, car grâce à eux, si on lit un livre ou un article, on connaît <<le dessous des cartes>>, on peut <<lever les masques>>. Malgré tout le plus sage est de s'en tenir aux auteurs morts. |

I was about to change my position again, so that he should not catch sight of me; I had neither the time nor the need to do so. What did I see? Face to face, in that courtyard where certainly they had never met before (M. de Charlus coming to the Hôtel de Guermantes only in the afternoon, during the time when Jupien was at his office), the Baron, having suddenly opened wide his half-shut eyes, was studying with unusual attention the ex-tailor poised on the threshold of his shop, while the latter, fastened suddenly to the ground before M. de Charlus, taking root in it like a plant, was contemplating with a look of amazement the plump form of the middle-aged Baron. But, more astounding still, M. de Charlus's attitude having changed, Jupien's, as though in obedience to the laws of an occult art, at once brought itself into harmony with it. The Baron, who was now seeking to conceal the impression that had been made on him, and yet, in spite of his affectation of indifference, seemed unable to move away without regret, went, came, looked vaguely into the distance in the way which, he felt, most enhanced the beauty of his eyes, assumed a complacent, careless, fatuous air. Meanwhile Jupien, shedding at once the humble, honest expression which I had always associated with him, had—in perfect symmetry with the Baron—thrown up his head, given a becoming tilt to his body, placed his hand with a grotesque impertinence on his hip, stuck out his behind, posed himself with the coquetry that the orchid might have adopted on the providential arrival of the bee. I had not supposed that he could appear so repellent. But I was equally unaware that he was capable of improvising his part in this sort of dumb charade, which (albeit he found himself for the first time in the presence of M. de Charlus) seemed to have been long and carefully rehearsed; one does not arrive spontaneously at that pitch of perfection except when one meets in a foreign country a compatriot with whom an understanding then grows up of itself, both parties speaking the same language, even though they have never seen one another before.This encounter leads ultimately to a casual tryst between the two men in the tailor's empty shop, for which Charlus tries to pay Jupien, overheard by Marcel who sneaks into the vacant shop next to that of the tailor. As the two men talk in the shop, Charlus inquires about other targets he has been eying in the neighborhood, including Marcel himself ("at the present moment my head has been turned by a strange little fellow, an intelligent little bourgeois who shews with regard to myself a prodigious want of civility. He has absolutely no idea of the prodigious personage that I am, and of the microscopic animalcule that he his in comparison," he says). Marcel writes after revealing all this dirt:

Now the abstraction had become materialised, the creature at last discerned had lost its power of remaining invisible, and the transformation of M. de Charlus into a new person was so complete that not only the contrasts of his face, of his voice, but, in retrospect, the very ups and downs of his relations with myself, everything that hitherto had seemed to my mind incoherent, became intelligible, brought itself into evidence, just as a sentence which presents no meaning so long as it remains broken up in letters scattered at random upon a table, expresses, if these letters be rearranged in the proper order, a thought which one can never afterwards forget.This sets the tone for the fourth book, literally the central volume of the seven-volume series, the suspicion and outing by Marcel of the homosexual and lesbian proclivities of major characters. In what I have already identified as the self-hating attitude of the closeted homosexual (see post on December 29), Charlus and his various liaisons are exposed as ridiculous and grotesque. Marcel continues:

I now understood, moreover, how, earlier in the day, when I had seen him coming away from Mme. de Villeparisis's, I had managed to arrive at the conclusion that M. de Charlus looked like a woman: he was one! He belonged to that race of beings, less paradoxical than they appear, whose ideal is manly simply because their temperament is feminine and who in their life resemble in appearance only the rest of men; there where each of us carries, inscribed in those eyes through which he beholds everything in the universe, a human outline engraved on the surface of the pupil, for them it is that not of a nymph but of a youth.Marcel's scorn for the aging homosexual Charlus only becomes harsher throughout the course of the fourth book.

26.1.04

But Will They Make Psychotropic Drugs for Art Appreciation?

One of the best things about being a teacher (besides the edification of young minds, of course) is the snow day, and when Washington gets anything more than a dusting of snow (and sometimes even just the threat of snow), I get to sleep in and read all day long. (See Alfred Sisley's appreciation of fallen snow to the right, Jardin à Louveciennes - effet de neige, from 1874.) So, after shoveling the 6 to 8 inches of white stuff from the sidewalk this morning, I stumbled across Blake Gopnik's article (Science, Trying to Pick Our Brains About Art, January 25) from the Sunday edition of the Washington Post. I know that this has already gotten coverage in Arts & Letters Daily and probably on every other artsblog, but you really should read it.

One of the best things about being a teacher (besides the edification of young minds, of course) is the snow day, and when Washington gets anything more than a dusting of snow (and sometimes even just the threat of snow), I get to sleep in and read all day long. (See Alfred Sisley's appreciation of fallen snow to the right, Jardin à Louveciennes - effet de neige, from 1874.) So, after shoveling the 6 to 8 inches of white stuff from the sidewalk this morning, I stumbled across Blake Gopnik's article (Science, Trying to Pick Our Brains About Art, January 25) from the Sunday edition of the Washington Post. I know that this has already gotten coverage in Arts & Letters Daily and probably on every other artsblog, but you really should read it.The ideas in the article come from scientific papers presented at the Third International Conference on Neuroesthetics, Emotions in Art and the Brain, held on January 10 at the Berkeley Art Museum, in California. To paraphrase Bill Murray: "Scientists, artists, and art historians conversing together: mass hysteria!" (Scientists, I know from personal experience working with them and having them as family members, are really a culture-sensitive lot, and they like to poke their heads out of their laboratories from time to time to get involved in art, music, and reading.) The research presented at the conference has to do with what happens in the brain when people create and experience art. When we get that figured out, perhaps a drug company somewhere will make a Ritalin cousin that worried parents can have administered to students when they have to take my Humanities course and display an aversion to learning about the history of art, literature, and music. Such a development would surely take half of the challenge and interest out of my teaching experience.

From scanning the papers at the conference, I found one of those that Gopnik did not mention, "Patterns that Connect—The Self-Organizing Landscape and the Brain," presented by Robert Steinberg, a former NASA scientist who has returned to earlier interests to work in art. Here is the abstract:

I will describe a new way to create art that evokes a rich variety of perceptions and emotions by using a medium that can self-organize and provide feedback. The evolving patterns reflect a natural order that invites artist participation and control, producing a sense of recognition in the brain that is heightened by the excitement of the unexpected. Most images are complex, nonrepeating, nonrandom and fractal—and are created by maintaining the medium as an open system far from equilibrium (energy and matter are added). Feelings of wonder during the act of painting, provide a robust, though temporary shield against self- doubt.I haven't been able to locate any online images of this type of art, but I will keep looking.

This approach to painting uses ideas from a new field in science called Soft Condensed Matter Physics. The dynamic qualities of soft matter seem to be tailor-made for art, conferring the spontaneous formation of coherent order and unprecedented flow properties on fluids. Artists now have a new way to challenge their imagination using an endless array of patterns that capture the aggregate artistry of nature. Aesthetically motivated curiosity, that most important stimulus to discovery for early artisans, may be about to make a comeback. I will show several slides of paintings that exemplify this new concept.

25.1.04

Sale of Surrealist Books and Artifacts

In an article (La collection de livres surréalistes de Daniel Filipacchi va être dispersée, January 21) in Le Monde, Harry Bellet reports on an upcoming auction at Christie's in Paris on April 29. American readers may remember that some pieces of Daniel Filipacchi's celebrated collection of surrealist manuscripts and related material, part of which will now be offered for sale, was shown in the exhibit Surrealism: Two Private Eyes at the Guggenheim Museum in New York in 1999. How Filipacchi ended up with his collection is recounted in the article, here in my translation:

Paris, 1938. A ten-year-old kid, looking for a mystery novel when he got out of school, passed by the display of Pierre Béarn, a bookstore in the Rue Monsieur-le-Prince. A title jumped out before his eyes, which seemed like part of the noir series he was reading: Le Revolver à cheveux blancs [The White-Haired Revolver, 1932]. He bought it without thinking that the author, André Breton, had nothing to do with Dashiell Hammett. "When I got back home and opened it up, I was a little disappointed. The typesetting was odd, with letters of different sizes and strange words aligned in no apparent order and without any obvious meaning..."The collection numbers 200 hundred items and is expected to fetch a price of at least 5 million euros ($6.3 million). It includes valuable books by Apollinaire, Duchamp, Tzara, and the other surrealists. Some of the most precious volumes include:

Then the war came: in occupied Paris, the teenager, having become a typesetter, was setting in lead a text titled Au rendez-vous allemand [Appointment with Germany, 1944]. Paul Eluard was leaning over his shoulder to correct his typos. He had missed three of them: "I have a copy of this book with the three errors corrected in Eluard's hand," recounts the young man grown old, now himself an editor and newsman, Daniel Filipacchi. "I cherish it."

The first published copy of the Prose du Transsibérien et de la petite Jehanne de France [by Blaise Cendrars, from 1913], one of the only ones to have been signed by Cendrars in the time when he still had a right hand and to have been preserved in its original book jacket painted, like the illustrations, by Sonia Delaunay. Or hand-written war letters addressed to André Breton, Théordore Fraenkel, and Louis Aragon by Jacques Vaché.You can see multiple versions of Picasso's etchings and sketches for Saint Matorel, made mostly in the summer of 1910, from the On-Line Picasso Project: Mademoiselle Léonie, Le Monastère, La table, and many others.

There is also the Cornet à dés, a four-hand game played in 1917 by Max Jacob and Pablo Picasso, accompanied by 20 manuscript poems by Max Jacob which, according to the expert's research, remain unknown to this day. With them, the most celebrated Saint Matorel, published by Kahnweiler in 1911, one of the 15 principal copies, on Japanese paper. And also the Trésor des jésuites, manuscript and typescript of a surrealist, anticlerical play in three scenes and prologue, the product of a collaboration between André Breton and Louis Aragon, from the time when they still liked one another. Less spectacular, but still interesting, the little copy of the original edition of Ubu roi, accompanied by a portrait of Father Ubu, or rather of "Monsieur Hébert, profezzor of phyzzicks," painted in oil on wood by [Alfred] Jarry when he was still in high school [in 1896]. And let us not forget the copy of Sept Microbes vus à travers un tempérament [Seven Microbes seen through a temperament], given by Max Ernst to Man Ray.

24.1.04

Renzo Piano on Luciano Berio

Italian avant-garde composer Luciano Berio, cofounder of the Studio di Fonologia Musicale and the new music journal Incontri Musicali, died in May last year. In an article (La merveilleuse inspiration d'un testament musical [The marvelous inspiration of a last will in music], January 23) in Le Monde, Renaud Machart reviews a concert on January 22 at the Théâtre Mogador in Paris. The Orchestre de Paris, under the direction of Christoph Eschenbach, was joined by the Chorus of the Orchestre de Paris and the French Army Chorus in a program featuring the world premiere of Berio's final composition, Stanze, which was completed two weeks before his death. The piece was introduced that night by Berio's friend, the architect Renzo Piano:

The composer's friend, to whom the piece was dedicated, said some of those poetic lies that only "nonmusicians" can say. "Architecture is heavy and slow; music is lively and light." He also said that Berio, architect of sounds that he was, made him jealous. Renzo Piano invited the public to enter "Berio's palace," a sound palace made of rooms, "true rooms, with doors and windows, like the living spaces of a building," the composer wrote in a short note of explanation on this suite of poems for baritone, three male choruses, and orchestra (2002–2003).Machart is less impressed with the acoustics of the Théâtre Mogador ("one would have liked to hear these sounds clearly in a concert hall worthy of this name, in an acoustic that does not level out and destroy the rich perspectives of this music. But Paris had only a bad-sounding theater to offer for the final work of one of the greatest creators of the 20th century. Shame and misery.") or on the rest of the program ("We would rather remain discreet about the impression left by the Ciaccona [2002] of Marc-André Dalbavie, probably one of the weakest works by its brilliant composer.")

For my part, I have to write, to write about a composition that Pierre Boulez describes, in the program, like a "real last will"; to write as if the composer had died after the creation of this work, to write like one always did, while Berio was alive, saying as exactly as possible what one was feeling, what one was thinking, right or wrong. Berio knew he was sick and knew that this would be his last composition. And in this composition, he did, quite simply, what he had almost never done: setting poetry to music, as so many composers before him had done. Like them, Berio accomplished a logical, fluid, intelligible act of prosody, without proceeding to that deconstructive work toward which, like so many other avant-garde composers, he had been inclined. Here there were no phonemes, or unrelated noises, as in the famous Sequenza for solo voice, from 1966, written for his first wife, the mezzo soprano Cathy Berberian. With Stanze, Berio rediscovered, after all those years, the marvelous inspiration of what remains probably one of his masterpieces and his most often played opus, the Folk Songs from 1964.

Stanze, however, is of a completely different texture, a completely different appeal, which is open to multiple "interpretations": at once a suite of orchestrated melodies, an operatic scene, a symphony of Mahlerian scope (with adagios and scherzo, in the section on a poem by the pianist Alfred Brendel), an echo chamber of varied idioms (the German of Paul Celan and Dan Pagis, the Italian of Edoardo Sanguinetti and Giorgio Caproni, the English of Alfred Brendel), a vast elegy crossed in a grotesque and Viennese leap, and completed on an icy text: "With immense and distant eyes, with foreheads cracked at the graves' edge, the dead will gather."

23.1.04

A Proposal (Quasi-Serious)

On the drive home Wednesday, I enjoyed a brief commentary about the glory days of smoking (The Odor of a Bygone World, January 21) on NPR. According to the blurb from their Web site:

A WORD FROM OUR SPONSOR:

Kids, ignore what I am about to say, and stay away from cigarettes.

It is no secret that the glamourous image of smoking was largely created and manipulated by tobacco companies. (In case you think that the age of those sorts of advertising tactics is past, check out the strategies that one tobacco company was using just last year, in Tobacco firm offers celebs cigarettes for life, from August 7, 2003.) I understand this as an abstract concept; however, I have a hard time remembering it when looking at someone like Kate Moss smoking (or, in another era, Audrey Hepburn): are these images sexy and alluring because the women are smoking or are these women just sexy and alluring with or without a cigarette?

Eventually, I will be deported from the United States for saying this, but smoking is actually an intensely pleasureful activity. Yes, the well-known francophilia here at Ionarts extends to the guilty pleasure of the occasional cigarette. As with so many enjoyments in life, it is bad enough for you that it will eventually kill you. However, why are we focusing our efforts—as a society upset, quite justifiably, with the dangers of smoking—on a campaign to remove cigarettes from the ever shortening list of acceptable diversions available to us? We should instead, and here I am being at least somewhat serious, be spending money on research to make cigarettes noncarcinogenic. If we can avoid it at all, why would we give up the pleasure of having a smoke while strolling in the park? If you really don't think that sounds like fun, take a look at John Singer Sargent's painting Luxembourg Gardens at Twilight (1879, from The Minneapolis Institute of Arts), shown below.

Robert Siegel, a former smoker, talks about the sensations and memories provoked by the scent of stale cigarette smoke. He says, "It was the smell of America in the 20th century, a century that has passed and has largely taken its odor with it to oblivion." Ralph Schoenstein talks about his father's habit and the glamour of New York City when cigarettes were everywhere [this piece is an adaptation of a column originally published in the New York Daily News as It may be bad for you, but smoking had a glamour on December 28]. Mary Jo Pehl is reminded of her wild college roommate. The entertainer Teller, of Penn and Teller, remembers how his dad's cigarette smoke once cured his car sickness. Daniel Pinkwater heads back to a Chicago dive, and Peter Freundlich remembers what cigarettes symbolized when he was young: life without consequences.Those words about "stale cigarette smoke" might make you think that this was a negative assessment of the phenomenon of smoking, but the essays in this segment were more bittersweet nostalgia than the hysterical condemnation that reigns now. The online piece has two galleries of images, too, photographs related to the reminiscences narrated in the audio, as well as beautiful images of famous smokers from movies, ads, and photographs (wherever possible, of course, listing the year in which the subject died of lung cancer).

A WORD FROM OUR SPONSOR:

Kids, ignore what I am about to say, and stay away from cigarettes.

It is no secret that the glamourous image of smoking was largely created and manipulated by tobacco companies. (In case you think that the age of those sorts of advertising tactics is past, check out the strategies that one tobacco company was using just last year, in Tobacco firm offers celebs cigarettes for life, from August 7, 2003.) I understand this as an abstract concept; however, I have a hard time remembering it when looking at someone like Kate Moss smoking (or, in another era, Audrey Hepburn): are these images sexy and alluring because the women are smoking or are these women just sexy and alluring with or without a cigarette?

Eventually, I will be deported from the United States for saying this, but smoking is actually an intensely pleasureful activity. Yes, the well-known francophilia here at Ionarts extends to the guilty pleasure of the occasional cigarette. As with so many enjoyments in life, it is bad enough for you that it will eventually kill you. However, why are we focusing our efforts—as a society upset, quite justifiably, with the dangers of smoking—on a campaign to remove cigarettes from the ever shortening list of acceptable diversions available to us? We should instead, and here I am being at least somewhat serious, be spending money on research to make cigarettes noncarcinogenic. If we can avoid it at all, why would we give up the pleasure of having a smoke while strolling in the park? If you really don't think that sounds like fun, take a look at John Singer Sargent's painting Luxembourg Gardens at Twilight (1879, from The Minneapolis Institute of Arts), shown below.

22.1.04

Robert Olsen

If you haven't yet, go to Modern Art Notes and read Tyler Green's review of a Robert Olsen show (Robert Olsen: Painter of Modern Light, January 20) at Plane Space in New York. This was my first exposure to this painter's work, and the images in Tyler's post were enough to make me want to see more. What is interesting about these paintings of the Getty Center is that scenes of modern desolation (elevators, parking lots, trams), which are truly ugly and illuminated by fluorescent light, are rendered lovingly, accurately, and transformingly. From what little I've read about him since reading Tyler's review, Olsen has been compared to Edward Hopper (for example, the artificial light of New York Movie, from 1939; Gas, from 1940; Nighthawks, from 1942) and Giorgio Morandi. For the style, process, and subject matter, I would also make a connection with the precisionism of someone like Charles Sheeler (for example, see Suspended Power from 1939).

Robert Olsen is a recent graduate of UCLA's MFA program. Some searching produced a few more images of his paintings: Untitled (Gasoline Pump, #4) (2003), Pump (Island) (2003), The Distance Between Two Cars, Version I (2003), The Distance Between Two Cars, Version II (2003), Reset (2002), New Order (2002), Topology (Mathematiques) (2002), Civic 4 (2002), and Parking Meter (Multi Station) (2001). Some of the Gasoline Pump paintings were featured in a show called "C6H6" last year at Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects, where most of Olsen's work is shown.

Robert Olsen is a recent graduate of UCLA's MFA program. Some searching produced a few more images of his paintings: Untitled (Gasoline Pump, #4) (2003), Pump (Island) (2003), The Distance Between Two Cars, Version I (2003), The Distance Between Two Cars, Version II (2003), Reset (2002), New Order (2002), Topology (Mathematiques) (2002), Civic 4 (2002), and Parking Meter (Multi Station) (2001). Some of the Gasoline Pump paintings were featured in a show called "C6H6" last year at Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects, where most of Olsen's work is shown.

21.1.04

If You Dig, You Will Find It

A short item on the news from France 2 last night tipped me off to another archeological find in southern France. The online notice (Marseille: une basilique du Ve s. [Marseilles: a basilica from the 5th century], January 19) has a picture of the excavation under way for a new parking lot, during which a necropolis was found. The location of this necropolis was known to scholars, but the excavation also uncovered the foundations of an as yet unidentified basilica on the site. On France 2, the archeologists at the site identified a central tomb as set off from the rest of the necropolis. By its decoration and separating wall, it is thought to be the final resting place of a saint or other special person. According to them, this tomb appears to be undisturbed. They will open it when they have completed measuring and recording the ruins as they found them. Here is my translation of what you can read on the Web site:

Remains of an early Christian funerary basilica dating back to the 5th century have been brought to light in Marseilles. The discovery, described by the Minister of Culture, Jean-Jacques Aillagon, as "exceptional," was made as part of planned excavations for the construction of a parking lot. The edifice was located in the present-day neighborhood of La Joliette, near the commercial port, and was 18 meters [59 feet] wide and more than 35 meters [115 feet] long. It was supposedly abandoned in the 7th century. About 50 sarcophagi, as well as tiled tombs or urns for young children, have been found.Readers may remember my reports on the basilica at Arles (see posts on November 17 and November 20), a building that was well known to scholars of the early Christian period but whose precise location had been unknown. Early this month, an official of the city government of Arles kindly sent me some materials from the conference on the excavation that took place on December 2, days before the devastating floods that hit Arles (see my post on December 6). You can see some of the images that were sent to me on a page from the city of Arles about the conference (La basilique paléochrétienne d’Arles, January 9), including a computer reconstruction of what the apse may have looked like, based on the mosaic pieces that were found. Here are some of the remarks made by those who attended the conference in Arles (my translation):

"The exceptional nature of this discovery is underscored by the exceptional state of conservation of liturgical components associated with the 'memoria' (special sepulcher) and the altar, as well as the quality of interior decoration that apparently adorned the edifice, which suffered a large removal of stone after it was abandoned," specified the Minister of Culture in an announcement. The excavations should be concluded during the month of February.

This is the second time in a few months that early Christian ruins have been discovered in the Bouches-du-Rhône: in November, a cathedral constructed around 350 was discovered in the garden of a former convent in Arles, during construction. It is supposedly the first constructed in France, according to researchers from the CNRS.

Jean-Paul Demoule for INRAP (National Institute for Preventive Archeological Research): "I am not sure that the same discovery would have brought together such an audience in another town." INRAP, with its 1,500 archeologists, deals with 2,000 operations each year throughout France to avoid massive damage, such as that inflicted on the remains of the Greek port in Marseilles during the 1960s, for example.I will continue to follow both of these archeological stories as they develop.

Jean-Maurice Rouquette [Honorary Curator of the Museums of Arles] remembers the discovery of Fernand Benoît, his history teacher, in 1943. "While digging defensive trenches—it was World War II—he came upon a great wall and an ancient column in the garden of the Saint-Césaire convent. He thought he had found the remains of a temple to Diana. I am convinced today that it was the basilica's wall, which reaches from the transept crossing to the Rue du Grand Couvent!"

20.1.04

Novelty in the Arts

"Basin was talking to you just now about Beethoven. We heard a thing of his played the other day which was really quite good, though a little stiff, with a Russian theme in it. It's pathetic to think that he believed it to be Russian. In the same way as the Chinese painters believed they were copying Bellini. Besides, even in the same country, whenever anybody begins to look at things in a way that is slightly novel, nine hundred and ninety-nine people out of a thousand are totally incapable of seeing what he puts before them. It takes at least forty years before they can manage to make it out." "Forty years!" the Princess cried in alarm. "Why, yes," went on the Duchess, adding more and more to her words (which were practically my own, for I had just been expressing a similar idea to her), thanks to her way of pronouncing them, the equivalent of what on the printed page is called italics: "it's like a sort of first isolated individual of a species which does not yet exist but is going to multiply in the future, an individual endowed with a kind of sense which the human race of his generation does not possess. I can hardly give myself as an instance because I, on the contrary, have always loved any interesting production from the very start, however novel it might be. But really, the other day I was with the Grand Duchess in the Louvre and we happened to pass before Manet's Olympia. Nowadays nobody is in the least surprised by it. It looks just like an Ingres! And yet, heaven only knows how many spears I've had to break for that picture, which I don't altogether like but which is unquestionably the work of somebody."Around the time of the novel's action, in 1891, Paul Gauguin was making a copy of Manet's Olympia, which is now in a private collection. Manet's painting is now on display in the Musée d'Orsay. Art is used by Proust's characters in all sorts of interesting ways. The refined tastes of Charlus come into play in the advances he makes to Marcel, culminating in the infamous interview at the end of The Guermantes Way. Having given Marcel a carefully chosen book by his favorite author, Charlus is outraged that the young man did not understand what he was trying to communicate by it.

"What!" he cried with fury, and indeed his face, convulsed and white, differed as much from his ordinary face as does the sea when on a morning of storm one finds instead of its customary smiling surface a thousand serpents writhing in spray and foam, "do you mean to pretend that you did not receive my message—almost a declaration—that you were to remember me? What was there in the way of decoration round the cover of the book that I sent you?" "Some very pretty twined garlands with tooled ornaments," I told him. "Ah!" he replied, with an air of scorn, "these young Frenchmen know little of the treasures of our land. What would be said of a young Berliner who had never heard of the Walküre? Besides, you must have eyes to see and see not, since you yourself told me that you had stood for two hours in front of that particular treasure. I can see that you know no more about flowers than you do about styles; don't protest that you know about styles," he cried in a shrill scream of rage, "you can't even tell me what you are sitting on. You offer your hindquarters a Directory chauffeuse as a Louis XIV bergère. One of these days you'll be mistaking Mme. de Villeparisis's knees for the seat of the rear, and a fine mess you'll make of things then. It's precisely the same; you didn't even recognise on the binding of Bergotte's book the lintel of myosotis over the door of Balbec church. Could there be any clearer way of saying to you: 'Forget me not!'?" I looked at M. de Charlus. Undoubtedly his magnificent head, though repellent, yet far surpassed that of any of his relatives; you would have called him an Apollo grown old; but an olive-hued, bilious juice seemed ready to start from the corners of his evil mouth; as for intellect, one could not deny that his, over a vast compass, had taken in many things which must always remain unknown to his brother Guermantes. But whatever the fine words with which he coloured all his hatreds, one felt that, even if there was now an offended pride, now a disappointment in love, or a rancour, or sadism, a love of teasing, a fixed obsession, this man was capable of doing murder, and of proving by force of logic that he had been right in doing it and was still superior by a hundred cubits in moral stature to his brother, his sister-in-law, or any of the rest. "Just as, in Velazquez’s Lances," he went on, "the victor advances towards him who is the humbler in rank, as is the duty of every noble nature, since I was everything and you were nothing, it was I who took the first steps towards you. You have made an idiotic reply to what it is not for me to describe as an act of greatness. But I have not allowed myself to be discouraged. Our religion inculcates patience. The patience I have shewn towards you will be counted, I hope, to my credit, and also my having only smiled at what might be denounced as impertinence, were it within your power to offer any impertinence to me who surpass you in stature by so many cubits; but after all, Sir, all this is now neither here nor there. I have subjected you to the test which the one eminent man of our world has ingeniously named the test of excessive friendliness, and which he rightly declares to be the most terrible of all, the only one that can separate the good grain from the tares. I could scarcely reproach you for having undergone it without success, for those who emerge from it triumphant are very few. But at least, and this is the conclusion which I am entitled to draw from the last words that we shall exchange on this earth, at least I intend to hear nothing more of your calumnious fabrications."The Velázquez reference is to the Surrender of Breda, sometimes known as Las Lanzas (see this extensive analysis of the painting).

19.1.04

Miscellany

I've come across some interesting stuff the past couple days, none of which really merits a long post, so I'm just throwing it all out there together. First, from the Department of Cultural Whimsy, in an article (Les rues d'Annecy résonnent de textes poétiques ou politiques, January 16) in Le Monde, Catherine Bédarida reported on a quirky sort of festival in the town of Annecy:

In the world of art auctions, there has been interesting news. Souren Melikian (In Paris, the Battle of the Auctions: Christie's Rising, in the International Herald Tribune on January 17) reports on the increasing dominance of Christie's new Paris house over French houses like Tajan and Drouot. There was some coverage of the report that the J. H. Whitney private collection of paintings would be auctioned at Sotheby's in New York on May 5 (Carol Vogel, Famed Whitney Collection of Art Is on the Block, in the New York Times on January 15). The prize of this collection, Picasso's stunningly beautiful Rose period painting Boy with a Pipe (1905), is expected to sell for at least $70 million. Although I wanted to see a list of all 44 paintings to be auctioned (to benefit the Greentree Foundation, I could only find this gallery of highlights.

There are some cool Web resources (in French) from Le Monde: one on George Sand and one on Prosper Mérimée (see post on August 6). I cannot give you a direct link: go here and follow the links under "Revues de Web." Le Figaro also has a feature on George Sand (it's the 200th anniversary of her birth this year). Also, the 2001 special issue of Le Point devoted to Victor Hugo is available online.

Finally, if you want a good laugh, read Dave Barry's article (A Chance for Amateurs to Mumble 'Huh?', January 17), published by the Miami Herald and carried by the International Herald Tribune. (We also love Dave's blog.) This is ostensibly a review of one part of the Art Basel show in Miami Beach (the main show was reviewed by Tyler Green at Modern Art Notes last month: you have to scroll through the page), but it is really a chance to poke fun at modern art:

To get to know Comment aimer [How to love], you have to let yourself wander the streets of old Annecy. At the Café du Cygne, through the little shopping streets, inside an apartment, actors are making heard the poetry of American Stacy Doris. For five days, the [theater troupe] Scène nationale d'Annecy is offering about ten readings as part of its "Inédits" [Undiscovered] series. The readings—a sort of entertainment that is growing in popularity in France—most often serve as a way to present new texts, freshly issued from the author's printer or by foreign authors little known in France.The "happenings" described in the article are strange and fun, most of them attended by an audience of young people, happy to take advantage of the free admission, dancing, drinking, and thinking about art and words into the wee hours.

In the world of art auctions, there has been interesting news. Souren Melikian (In Paris, the Battle of the Auctions: Christie's Rising, in the International Herald Tribune on January 17) reports on the increasing dominance of Christie's new Paris house over French houses like Tajan and Drouot. There was some coverage of the report that the J. H. Whitney private collection of paintings would be auctioned at Sotheby's in New York on May 5 (Carol Vogel, Famed Whitney Collection of Art Is on the Block, in the New York Times on January 15). The prize of this collection, Picasso's stunningly beautiful Rose period painting Boy with a Pipe (1905), is expected to sell for at least $70 million. Although I wanted to see a list of all 44 paintings to be auctioned (to benefit the Greentree Foundation, I could only find this gallery of highlights.

There are some cool Web resources (in French) from Le Monde: one on George Sand and one on Prosper Mérimée (see post on August 6). I cannot give you a direct link: go here and follow the links under "Revues de Web." Le Figaro also has a feature on George Sand (it's the 200th anniversary of her birth this year). Also, the 2001 special issue of Le Point devoted to Victor Hugo is available online.

Finally, if you want a good laugh, read Dave Barry's article (A Chance for Amateurs to Mumble 'Huh?', January 17), published by the Miami Herald and carried by the International Herald Tribune. (We also love Dave's blog.) This is ostensibly a review of one part of the Art Basel show in Miami Beach (the main show was reviewed by Tyler Green at Modern Art Notes last month: you have to scroll through the page), but it is really a chance to poke fun at modern art:

A lot of Serious Art consists of bizarre or startlingly unattractive objects, or "performances" wherein artists do something Conceptual, such as squirt Cheez Whiz into an orifice that has not been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for snack toppings. But no matter what the art is, a Serious Art Person will view it with the somber expression of a radiologist examining X-rays of a tumor. Whereas an amateur will eventually give himself away by laughing, or saying "Huh?" or (this is the most embarrassing) asking an art-gallery person: "Is this wastebasket a piece of art? Or can I put my gum wrapper in it?"We at Ionarts hope we are not Serious Art People, and if we are, we promise to lighten up.

18.1.04

Blame Canada! — The Invasion of Pianists Continues — by Jens Laurson

This is a review of a concert at the National Gallery of Art on December 28, 2003.

In the 2,478th "William Nelson Cromwell and F. Lammot Belin" Concert at the National Gallery of Art, the fare was another bright star of the keyboard, Canadian Marc-André Hamelin. Known worldwide among music lovers for his superb recordings on the Hyperion label, he has proven himself comfortable with the often fiendishly difficult works of composers such as Godowsky, Alkan, Bolcom, Henselt, et al. The technical skill of this Philadelphia resident is considered by many enthusiasts to be unequaled among active pianists.

As he was playing just a fortnight after his compatriot Angela Hewitt appeared at the National Gallery (see review on December 18), the expectations were accordingly high. The turnout on this mild winter night supports this. Despite post-holiday sluggishness, the West Garden Court filled steadily, and by 6:45 people could no longer find seats. I myself was sandwiched in with three opinionated amateur pianists and classical music lovers who put my feeble knowledge of the subject matter to shame.

Finally, after I had waited some 90 minutes for the concert to start at 7:00, Hamelin appeared from behind the curtain, bowed to much applause, and then, after a short moment in which he gathered his concentration, started to peal off the familiar and delightful notes from W. A. Mozart's Piano Sonata in C major K.330. In his hands, with his manner of playing, the Allegro moderato (played on the fast side) seemed like a delicate little toy that Mr. Hamelin carefully and gently treated to an audible outing. Perhaps this impression stemmed from the absolute ease with which Mr. Hamelin played this piece. Even with the little runs and trill figures at full speed, this isn’t a very difficult piece to play, but for Hamelin, with his unique technical ability and prowess, it must be an apt way to warm up and relax at the same time.

He evoked similar sweet feelings in the Andante cantabile. Hamelin caressed the melody out of the Steinway. The honey he imparted to the notes (to a point where they lacked some of their clarity) was somewhat sedating. The somber character of the music, too, may reflect the influence of Mozart’s mother having died three years prior to the composition of this sonata in 1781. I am told that the style of Hamelin’s playing that I was trying to pin down is called the "Dresden china" approach to Mozart. The name seems fitting enough to remember for future reference.

The much needed Allegretto followed as the last movement, and eyelids in the audience, heavy until a few seconds ago, rose instantly at Marc-André Hamelin’s surprising and unusually energetic beginning. As the piece quaintly bubbled toward its end, concertgoers had plenty of opportunities to observe the borderline-disastrous acoustics of the concrete and stone (plus trees) West Garden Court. Since the sound reflects from the plethora of different surfaces (pillars, side walls, fountain, etc.), notes have little chance of developing without being blurred by others played before or after, and the result is a lush, churchlike sound, only without much of the grace a good church acoustic can offer.

When the last note of the final three hammered chords had barely struck, one audience member felt that his incomparable knowledge of the music was in dire need of showing off and started clapping vigorously. Truly, only the courageous and those free of doubt, with the score of the piece firmly imprinted in their head, dare such erudite behavior. Unfortunately, to those who merely wish to enjoy a nice piece of music (regardless of how and when it ends), it is utterly annoying.

Following the Mozart came another listener-friendly piece, if of an entirely different character. Robert Schumann’s Fantasiestücke op.12 (eight relatively short pieces with descriptive names) started dreamily, meandering with "Des Abends" (in its subtlety almost untranslatable, but for all practical purposes, "In the Evening" or "Evening-time"). That evening ended on a low chord with a little whimsical note plucked in the upper register. The tone barely gone, Hamelin broke into "Aufschwung" like a berserker . . . the contrast to the preceding mellowness could not be greater. "Soaring," the English title for it in the program notes, is probably not the best translation, and the music and the interpretation were not very soaring, either. "Impetus," "impulse," and even "inspiration" (all literal translations of the noun "Aufschwung") are all more apt at describing this movement than "soaring," which probably comes from "to soar," the literal translation of the verb of the same form, "aufschwingen"). After all, this was no eagle majestically flying about somewhere in the Alps: it was a musical "Eureka moment."

But why not move on: "Warum?" ("Why?") was not badly played at all. Hamelin's pinpoint accuracy and sure-handed excellence continued in this contemplative, sprawling piece. "Grillen" ("Whims") was muscular again and began with some ferocity, bouncing back between the strange and whimsical and (the other translation of "Grillen") melancholic. To descend into darker tones, one needs only to wait for "In der Nacht" with its brooding bubbles, containing much of the type of music that evokes perpetual motion and stands (usually in mediocre films) for pianistic virtuosity. While every note was played correctly, the acoustics and liberal pedaling threw them back together in our ears.

"Fabel" takes a mild approach, until it, too, displays a need for speed after a few bars. It ebbs and flows, acquires significant speed, and finally dribbles out with a thrice-repeated chord. "Traumeswirren" are indeed confused ("troubled") dreams and the end of the song ("Ende vom Lied") comes literally and with some quixotic power. Apparently, the pieces are divided between Schumann’s alter egos Florestan (loquacious and impetuous) and Eusebius (reflective and otherworldly), as Elmer Booze (known to Library of Congress concertgoers as the gentleman who turns the pages in piano-involved concerts) tells us in the program notes.

The intermission brought immediate and wildly varying arguments and perceptions. The only agreement to be found was that Hamelin sounded very different from his recordings, which offer (like most Hyperion-recorded pianists) a rather dry and detailed tone. This difference, however, had some finding the Schumann quite astounding and very enjoyable, while other opinions went all the way to "travesty" and "atrocious." Unhelpful pedaling, muddled thrills, inept phrasing, and swallowed arpeggios seem to have raised the ire with at least one fuming audience member/pianist. My suggestion to blame it partly on the acoustics was better accepted after the concert than at this point.

Fortunately for him, the acquaintance who had been rather outraged at the Mozart and Schumann performance did not make good on his threat to leave and found himself rather enjoying the second half of the concert, in which we got to hear one of the great virtuoso works for piano: Issac Albéniz's Iberia, Book Three: El Albaicín, El polo, and Lavapiés. Iberia, Albéniz's major work (re-orchestrated by some of his students) is an absolute piano masterpiece in scope and varieties of style. From four books of four pieces altogether, the pieces chosen by Mr. Hamelin reflect different regions in Spain (Granada, the Andalusian south, a corner of Madrid), as well as their songs and dances.

"El Albaicín" starts with a fairly reduced theme that grows into more complex structures, only to recede again. As it is far richer in color and shadings than the previous pieces, I constantly found new themes spun out of the core of the playing. There are many notes in this music (I am reminded of the Emperor's hilarious, if fictitious, criticism of Mozart's music in Amadeus: "too many notes"), and not all of those notes have time to develop. Pedal, speed, and acoustics are the main culprits. Speaking of culprit, one attendee had an unfortunate attack of bronchitis and, more unfortunate still, did not have the decency to leave. After some ten minutes of periodic, strenuously suppressed coughing it either got better or I grew used to it.

"El polo," not a diminutive chicken but a dance from Andalusia, is in parts more moderately paced, but like all three pieces it is a heterogeneous sound-carpet. Whimsy comes out to play towards the end, before brute force squashes it. "Lavapiés" opens with a storm, full pedal; one slightly dissonant note sticking out in a repeated chord becomes the calling card of the opening. Rhythmically hopping, somewhere between horses and fat, black flies in boiling summer heat (difficult to conjure in a cold West Garden Court, with late December outside) and more taxing repertoire than anything tonight, this work got more engagement from Mr. Hamelin. Difficult to describe as it is, I opted to sit back and enjoy. In the enjoyment I found myself seconded by all around me, even the dissenting voices earlier. Description, however, varied. While I heard something about an (emotionally?) dry approach, I thought it to have been everything but dry . . . involved, a little slurring (I blame the hall mostly), heavy pedal (intended by the composer, as can be read in the score, not with pedal markings but legato bows in the bass line) made for what I thought was a particularly lush drive down to El Albaicín.

Such nitpicking notwithstanding, it was another night well spent at the National Gallery of Arts, as the evening ended on such a positive, uhm, note.

In the 2,478th "William Nelson Cromwell and F. Lammot Belin" Concert at the National Gallery of Art, the fare was another bright star of the keyboard, Canadian Marc-André Hamelin. Known worldwide among music lovers for his superb recordings on the Hyperion label, he has proven himself comfortable with the often fiendishly difficult works of composers such as Godowsky, Alkan, Bolcom, Henselt, et al. The technical skill of this Philadelphia resident is considered by many enthusiasts to be unequaled among active pianists.

As he was playing just a fortnight after his compatriot Angela Hewitt appeared at the National Gallery (see review on December 18), the expectations were accordingly high. The turnout on this mild winter night supports this. Despite post-holiday sluggishness, the West Garden Court filled steadily, and by 6:45 people could no longer find seats. I myself was sandwiched in with three opinionated amateur pianists and classical music lovers who put my feeble knowledge of the subject matter to shame.

Finally, after I had waited some 90 minutes for the concert to start at 7:00, Hamelin appeared from behind the curtain, bowed to much applause, and then, after a short moment in which he gathered his concentration, started to peal off the familiar and delightful notes from W. A. Mozart's Piano Sonata in C major K.330. In his hands, with his manner of playing, the Allegro moderato (played on the fast side) seemed like a delicate little toy that Mr. Hamelin carefully and gently treated to an audible outing. Perhaps this impression stemmed from the absolute ease with which Mr. Hamelin played this piece. Even with the little runs and trill figures at full speed, this isn’t a very difficult piece to play, but for Hamelin, with his unique technical ability and prowess, it must be an apt way to warm up and relax at the same time.

He evoked similar sweet feelings in the Andante cantabile. Hamelin caressed the melody out of the Steinway. The honey he imparted to the notes (to a point where they lacked some of their clarity) was somewhat sedating. The somber character of the music, too, may reflect the influence of Mozart’s mother having died three years prior to the composition of this sonata in 1781. I am told that the style of Hamelin’s playing that I was trying to pin down is called the "Dresden china" approach to Mozart. The name seems fitting enough to remember for future reference.

The much needed Allegretto followed as the last movement, and eyelids in the audience, heavy until a few seconds ago, rose instantly at Marc-André Hamelin’s surprising and unusually energetic beginning. As the piece quaintly bubbled toward its end, concertgoers had plenty of opportunities to observe the borderline-disastrous acoustics of the concrete and stone (plus trees) West Garden Court. Since the sound reflects from the plethora of different surfaces (pillars, side walls, fountain, etc.), notes have little chance of developing without being blurred by others played before or after, and the result is a lush, churchlike sound, only without much of the grace a good church acoustic can offer.

When the last note of the final three hammered chords had barely struck, one audience member felt that his incomparable knowledge of the music was in dire need of showing off and started clapping vigorously. Truly, only the courageous and those free of doubt, with the score of the piece firmly imprinted in their head, dare such erudite behavior. Unfortunately, to those who merely wish to enjoy a nice piece of music (regardless of how and when it ends), it is utterly annoying.

Following the Mozart came another listener-friendly piece, if of an entirely different character. Robert Schumann’s Fantasiestücke op.12 (eight relatively short pieces with descriptive names) started dreamily, meandering with "Des Abends" (in its subtlety almost untranslatable, but for all practical purposes, "In the Evening" or "Evening-time"). That evening ended on a low chord with a little whimsical note plucked in the upper register. The tone barely gone, Hamelin broke into "Aufschwung" like a berserker . . . the contrast to the preceding mellowness could not be greater. "Soaring," the English title for it in the program notes, is probably not the best translation, and the music and the interpretation were not very soaring, either. "Impetus," "impulse," and even "inspiration" (all literal translations of the noun "Aufschwung") are all more apt at describing this movement than "soaring," which probably comes from "to soar," the literal translation of the verb of the same form, "aufschwingen"). After all, this was no eagle majestically flying about somewhere in the Alps: it was a musical "Eureka moment."

But why not move on: "Warum?" ("Why?") was not badly played at all. Hamelin's pinpoint accuracy and sure-handed excellence continued in this contemplative, sprawling piece. "Grillen" ("Whims") was muscular again and began with some ferocity, bouncing back between the strange and whimsical and (the other translation of "Grillen") melancholic. To descend into darker tones, one needs only to wait for "In der Nacht" with its brooding bubbles, containing much of the type of music that evokes perpetual motion and stands (usually in mediocre films) for pianistic virtuosity. While every note was played correctly, the acoustics and liberal pedaling threw them back together in our ears.

"Fabel" takes a mild approach, until it, too, displays a need for speed after a few bars. It ebbs and flows, acquires significant speed, and finally dribbles out with a thrice-repeated chord. "Traumeswirren" are indeed confused ("troubled") dreams and the end of the song ("Ende vom Lied") comes literally and with some quixotic power. Apparently, the pieces are divided between Schumann’s alter egos Florestan (loquacious and impetuous) and Eusebius (reflective and otherworldly), as Elmer Booze (known to Library of Congress concertgoers as the gentleman who turns the pages in piano-involved concerts) tells us in the program notes.

The intermission brought immediate and wildly varying arguments and perceptions. The only agreement to be found was that Hamelin sounded very different from his recordings, which offer (like most Hyperion-recorded pianists) a rather dry and detailed tone. This difference, however, had some finding the Schumann quite astounding and very enjoyable, while other opinions went all the way to "travesty" and "atrocious." Unhelpful pedaling, muddled thrills, inept phrasing, and swallowed arpeggios seem to have raised the ire with at least one fuming audience member/pianist. My suggestion to blame it partly on the acoustics was better accepted after the concert than at this point.

Fortunately for him, the acquaintance who had been rather outraged at the Mozart and Schumann performance did not make good on his threat to leave and found himself rather enjoying the second half of the concert, in which we got to hear one of the great virtuoso works for piano: Issac Albéniz's Iberia, Book Three: El Albaicín, El polo, and Lavapiés. Iberia, Albéniz's major work (re-orchestrated by some of his students) is an absolute piano masterpiece in scope and varieties of style. From four books of four pieces altogether, the pieces chosen by Mr. Hamelin reflect different regions in Spain (Granada, the Andalusian south, a corner of Madrid), as well as their songs and dances.

"El Albaicín" starts with a fairly reduced theme that grows into more complex structures, only to recede again. As it is far richer in color and shadings than the previous pieces, I constantly found new themes spun out of the core of the playing. There are many notes in this music (I am reminded of the Emperor's hilarious, if fictitious, criticism of Mozart's music in Amadeus: "too many notes"), and not all of those notes have time to develop. Pedal, speed, and acoustics are the main culprits. Speaking of culprit, one attendee had an unfortunate attack of bronchitis and, more unfortunate still, did not have the decency to leave. After some ten minutes of periodic, strenuously suppressed coughing it either got better or I grew used to it.

"El polo," not a diminutive chicken but a dance from Andalusia, is in parts more moderately paced, but like all three pieces it is a heterogeneous sound-carpet. Whimsy comes out to play towards the end, before brute force squashes it. "Lavapiés" opens with a storm, full pedal; one slightly dissonant note sticking out in a repeated chord becomes the calling card of the opening. Rhythmically hopping, somewhere between horses and fat, black flies in boiling summer heat (difficult to conjure in a cold West Garden Court, with late December outside) and more taxing repertoire than anything tonight, this work got more engagement from Mr. Hamelin. Difficult to describe as it is, I opted to sit back and enjoy. In the enjoyment I found myself seconded by all around me, even the dissenting voices earlier. Description, however, varied. While I heard something about an (emotionally?) dry approach, I thought it to have been everything but dry . . . involved, a little slurring (I blame the hall mostly), heavy pedal (intended by the composer, as can be read in the score, not with pedal markings but legato bows in the bass line) made for what I thought was a particularly lush drive down to El Albaicín.

Such nitpicking notwithstanding, it was another night well spent at the National Gallery of Arts, as the evening ended on such a positive, uhm, note.

17.1.04

BIG FISH Is Worth Being Lured — by Todd Babcock

There seems to be a bit of disparity among critics and moviegoers over the verdict on Tim Burton's recent film Big Fish. While the film is making respectful money, the trades seem to report that it is underachieving according to expectations. Critics seem split on whether it's a saccharine, structureless circus of images (à la Planet of the Apes) or a truly inspired character piece like his brilliant Ed Wood. The answer is neither, and let me go on record saying that I bought it (with all apologies here) hook, line, and sinker.

"Big Fish" doesn't shy away from its sentiment or its style. The movie begins in metaphor and only balloons from there as scene after scene builds on its own ridiculousness. The structure couldn't fit Burton's creative style more in the form of one long series of stitched-together tall tales grounded back to reality with the fabric of a father-son story. Yet, while the director is swelling his canvas with mythic creativity, it is grounded firmly with a stellar cast.

The story centers around Edward Bloom (the flawless Albert Finney) in the waning years of a long and colorful life. Bloom, it seems, has been less a father than an orator of great and long-winded tales. (When his daughter-in-law asks him if "This is another tall tale?" he retorts quickly, "It certainly isn't a short one!") Playing Bloom's estranged son is Billy Crudup, who one can argue, never plays an off note. While the movie may parade its imagination on display, it is these two actors, along with Jessica Lange, who constantly place its feet back on firm ground.

The movie certainly asks something of its audience in terms of its style pill to swallow. Like its box office competitor Return of the King, one must look past the odd-looking characters and circumstances in order for the sentiment to get through. Ewan McGregor (who plays the young Bloom) embodies this notion, as in every scene he has a toothy smile pasted on like one of Burton's still drawings. While one would expect the effect to be of a flat-lining disinterest it eventually overcomes you with endearment, which could well describe the entire film.

Burton himself has gone so far as to profess that he "can't tell a story," and there are few who would disagree. Truly, even his most successful ventures (such as Pee-wee's Big Adventure, Batman, and Beetlejuice) have had the slightly veiled form of a collage of beautifully demented scenes woven together. It was with "Ed Wood" that he took a step forward with a stylized but character-driven narrative. Perhaps Tim, it was posited, was maturing as a filmmaker and we could soon expect Good Will Hunting out of him. As it turns out, he has absolutely no interest in such ventures. As he explains, "When I started in the business, they treated me like I was different; when I had success, then they wanted me because I was different. That kind of prepackaged 'difference' makes me very uncomfortable. And I have always tried to protect myself so I wouldn't know what it was they thought of as being like me. I get very uncomfortable with labeling" (New York Times Magazine). It turns out that to defy definition we were treated to the costume-driven debacle of Planet of the Apes.

I had the opportunity to work briefly with the director on "the Ape film" (don’t rent it, and if you do, don't blink), and what was so shocking and immensely captivating is that he never seemed like he was making a big action movie. Truly, he showed up on the set in jeans and his crazy hair and pretty much said, "whatever you guys wanna do." He would watch, laugh, scratch his head a bit, adjust, and then keep shooting. As I'm sure the suits and accountants at FOX wouldn't like to hear such a report, it does infuse one with a sense of empathy for the bad matching of director and project. Yet, if that's the turn it took to get us to "Big Fish," so be it.